The Long Death of the Gatekeepers

push to talk #48 // a digression on william faulkner + what the book publishing industry can teach us about the value and ultimate fate of industry gatekeepers

What follows is a sort of prologue to How to Find Market Signal: Part One. The animating argument of that piece was that the games industry is changing from a publishing model dictated by gatekeepers to one dictated by algorithms.

What does it mean for a creative industry when its gatekeepers lose their ability to pick winners or drive sales? Some lessons might be learned from the literary fiction publishing industry, which began a similar transformation decades ago.

If you read into the history of any creative field, one common theme you’ll encounter is the idea that the game has always been rigged.

The ability to distribute video games was long gatekept by publishers. Likewise, to make it in music, you’ve traditionally had to “get discovered” and promoted by someone connected to a record label. The entire art world—to hear some tell it—is an invention of the curators. And let’s not even get started on Hollywood.

Then there’s the world of books, especially literary fiction publishing. Never has there been a creative industry more rigged than fiction.

To get a work of fiction published, authors have always had to navigate a ridiculous labyrinth of self-appointed kingmakers and good-taste-havers. Look into the backstory of many widely recognized classics, and you’ll often-as-not read something like “the author was rejected by dozens of publishers and agents before finding a small press that would take their work.” The prototypical example of this is Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which was allegedly rejected 121 times before finding a publisher. The book was then, of course, an immediate hit on release, selling 50,000 copies in its first three months and millions more in dozens of languages in the years since.

The implied takeaway from stories like this is “the gatekeepers don’t know anything,” a reassuring salve for wounded artists who’ve been rejected by the powers-that-be.

And as an artist, you almost have to believe that the gatekeepers are wrong, because otherwise the wounds their rejections leave would be too devastating.

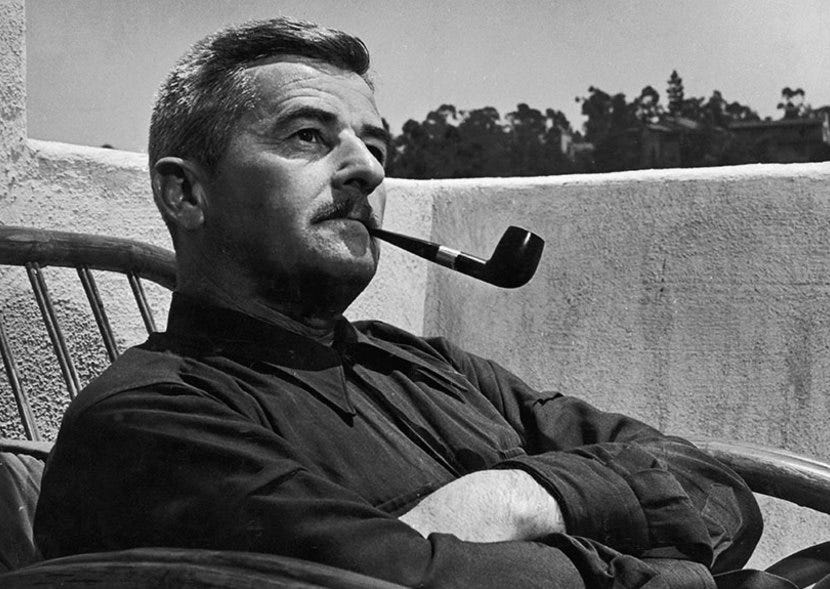

One of my favorite books is Joseph Blotner’s biography of William Faulkner. At times Blotner’s book reads like a horror story, as Faulkner’s constant lying, betrayals of loved ones, and legendary alcoholism lead him from one self-inflicted disaster to another.1

This was a man who cut his own life short by spending decades blisteringly drunk (sometimes literally blisteringly, as when he passed out while slumped against a hot hotel-room radiator) and repeatedly falling off of horses until, finally, he managed to secure himself a heart attack and die at the age of 64.

About 200 pages into Blotner’s ~800 page book, I was finding it hard to empathize with our boy Billy F. The guy was a rascal! He treated his friends badly and his lovers worse. And he seemed bent on self-destruction.

But then Blotner told a story that complicated my view of the man.

It was fall, 1927. Faulkner had just turned 30. Thanks to the help of a friend, the novelist Sherwood Anderson, Faulkner had managed to get two early novels published: Soldiers’ Pay and Mosquitoes. He hadn’t yet truly broken out or achieved commercial success, but the critics had been good to him and his confidence was growing. Now he was working on an ambitious third novel, a book called Flags in the Dust which was set in a place Faulkner called Yoknapatawpha County—a sort of dark, apocryphal landscape that existed in a parallel universe atop the northern Mississippi hills where he’d grown up.

Faulkner believed in the book. He believed he’d created something special. So he took it to the gatekeepers.

On October 16th of that year, he wrote to his publisher, Horace Liveright: “At last and certainly,” he boasted, “I have written THE book, of which those other things were but foals. I believe it is the damdest best book you’ll look at this year, and any other publisher.”2

A month or so later, the terrible reply came:

“It is with sorrow in my heart that I write to tell you that three of us have read Flags in the Dust and don’t believe that Boni and Liveright should publish it. Furthermore, as a firm deeply interested in your work, we don’t believe that you should offer it for publication.”

It got worse.

“Soldier’s Pay was a very fine book and should have done better. Then Mosquitoes wasn’t quite as good, showed little development in your spiritual growth and I think none in your art of writing. Now comes Flags in the Dust and we’re frankly very much disappointed by it. It is diffuse and nonintegral with neither very much plot development nor character development…. The story really doesn’t get anywhere and has a thousand loose ends. If the book had plot and structure, we might suggest shortening and revisions but it is so diffuse that I don’t think this would be any use.”

Normally publisher rejections take the form of a blandly polite or impersonal note.

That’s not what this was. Liveright’s letter was personal. Even before getting into any specific criticism of Flags in the Dust, Liveright went out of his way to say that, by the way, your second book was bad too, and it seems like you’ve experienced very little spiritual growth as a person. This wasn’t just a rejection of Faulkner’s book. It was an attack on his spirit.

So how did Faulkner respond?

Most people, upon receiving a letter like this, would almost certainly sink into despondency. Most people would rage, argue, spit, curse, and then fall into making excuses. And at first, it looked like that’s what Faulkner would do.

Faulkner’s reaction, in his own words:

I was shocked: my first emotion was blind protest, then I became objective for an instant, like a parent who is told that its child is a thief or an idiot or a leper; for a dreadful moment I contemplated it with consternation and despair, then like the parent I hid my own eyes in the fury of denial.”

But then Faulkner gathered himself. He wrote back. Ignoring Liveright’s exhortation to forget about the book, he demanded that Liveright return his manuscript so he could seek another publisher. “I still believe it is the book which will make my name for me as a writer,” he wrote.

But there was a problem. Boni and Liveright had already paid Faulkner a $200 advance for the book. If he took his manuscript back, he’d need to pay back the advance. So Faulkner offered a deal: he could just send them a different manuscript. A better one.

This was a borderline delusional gambit from Faulkner—but it worked. By the following February, Liveright had agreed to give up the rights to Flags in the Dust and apply Faulkner’s advance to his next novel, which he started work on almost immediately. That book, which Boni and Liveright would ultimately neglect to secure the rights to, would go on to become one of the most famous works in the history of English literature: The Sound and the Fury.

The Sound and the Fury was not Faulkner’s breakout novel, though it later came to be considered by many as his masterpiece. His first real commercial success arrived in 1931, when his sixth novel, Sanctuary, shocked readers with a lurid tale of rape and murder set between north Mississippi and Memphis. Faulkner’s literary reputation rose and he was subsequently able to scrape together a living as a Hollywood screenplay writer living in Culver City, California.3

But pretend, for a moment, that you didn’t already know about Faulkner’s future successes. Forget the Nobel prize in literature, and his astonishingly beautiful acceptance speech for that honor. Forget that he ultimately wrote 19 novels, 125 short stories, and 20 screenplays. When he got that letter from Horace Liveright, he was just Billy Faulkner. That’s what people called him, then.

Before Billy became William Faulkner—a man universally acknowledged as one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century—he was a no-name scoundrel with two badly-selling novels and a cruel rejection letter trembling in his hands. And in that moment, in late 1927, he decided that he knew better than the gatekeepers who had rejected him. He got Flags in the Dust published (though in a highly condensed form, as Sartoris) and kept on writing.

But something had changed. What he wrote next was undeniably better than the stuff he’d been producing before. Nobody talks about Mosquitoes or Soldier’s Pay now. But the stories Faulkner wrote over the ensuing 10 years became world famous, particularly The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930),4 Sanctuary (1931), Light in August (1932), and Absalom, Absalom! (1936). The themes of these books are grander, the characters deeper, the writing style more bold. Instead of shrinking back or consoling himself with excuses, Faulkner reached deeper into himself to produce art that has now lasted nearly a century.

Was Horace Liveright wrong about Flags in the Dust? Or, by telling Faulkner what he really thought, is it possible that Liveright gave him the fuel he needed?

The gatekeepers don’t know anything. That’s one possible takeaway.

Another possibility: An encounter with a closed gate can change everything.

The Old Guard in the New Millennium

In Faulkner’s time, gatekeepers in the publishing apparatus and in the media held all the power. Your book would never see the light of day unless you found an agent and publisher who approved of your work.

And because ownership of media was so concentrated, you had to carefully build and guard your reputation with the newspaper critics—this was part of the reason Liveright advised Faulkner to drop his book entirely. The implication was that by insisting on pushing an inferior book, Faulkner risked forever losing the support of the critics, effectively ending his fledgling career.

For all the faults of this system, it had its upsides: There was a sense of certainty about the business. If you could win the approval of a small number of gatekeepers, you gained access to a clearly structured career. So long as you kept delivering solid work, the publishers would promote you, the critics would dutifully cover each new release, and success (however modest) would follow.

And, of course, if you failed to please these gatekeepers, you could be equally certain that your time in book publishing was over.

Let’s turn the clock forward, not to the present day, but to the turn of the millennium. Seventy-two years after the publication of the The Sound and the Fury, all sense of certainty in the book publishing industry had disappeared.

In a remarkable book called Writing the Breakout Novel, published in 2001, literary agent (and author of 16 novels) Donald Maass made the case that publishers and media no longer had the power to reliably generate hits.

Maass’s blunt appraisal of the publishing industry was, in part, that it was simply producing too many books. He estimated that each year the American fiction industry produced 55,000 new titles.5

And with the industry becoming more competitive, Maass wrote, “fiction careers are biting the dust all over the place.”

Here’s how Maass described the situation:

Even big names on the literary scene are struggling. On the day I am writing this paragraph (June 9, 2000), the book industry columnist for The New York Times, Martin Arnold, reports that although major novels have been published this year by three of America’s preeminent novelists—Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and John Updike—only one made The New York Times best-seller list (Bellow’s Ravelstein) and only for one week.

Looked at historically, even commercial best-sellers do not have much to be smug about. When I began in publishing in the late 1970s, a top paperback could net over ten million units. Today, two million is good. Big commercial fiction is getting blown off the adult best-seller lists by, of all things a book for children, Harry Potter.

Perhaps part of the sales challenge could be blamed on the economic environment. At the time Maass was writing, in June of 2000, the US federal funds effective rate had just hit 6.5% for the first time since the early 90s (a level to which it has never returned).6

But Maass made the case that the problems ran deeper, going so far as to argue that publishing and promotional campaigns offered little value to authors, because publishers mostly don’t have tools to reliably sell books.

Addressing writers who complain about lack of promotional support from their publishers, he wrote:

In truth, all this angst over promotion is misplaced. Advertising certainly does not sell books. Ask an editorial director in a candid moment, and he will tell you: Ads in the New York Times Book Review are placed there mostly to make the author feel good. Media also has a limited effect on fiction sales. TV addicts are not high volume novel readers, Oprah’s Book Club members being the big exception to that rule. In general, radio is better at selling books, especially National Public Radio, but that special audience does not embrace all types of fiction.

Paid media campaigns weren’t hitting, but neither was earned media. We think of 2001 as being a period of peak power for mass media, but Maass didn’t think so. He kept up his attack on the publishers, claiming they didn’t know how to predict hits, despite telling themselves otherwise:

Breakout novels can be planned or at any rate encouraged, and a few of them are simply the payoff of a slow and steady growth in an author’s readership. More often, though, breakouts take publishers by surprise. All at once the author’s publicist must scramble. Extra printings are hastily scheduled. Salespeople get into high gear. The author’s editor, meanwhile, smiles wisely and pretends he knew the breakout would happen all along.

Everyone, including the authors, believed that success was a certainty. But they were full of bull:

The truth, though, is that underneath these assured exteriors, agents, editors, publicists, salespeople and even authors themselves generally do not have the foggiest idea why this sudden leap in popularity has happened. Ask publishers and they will probably comment, “Oh, we’ve been building him for years. It was his time.”

Bull. Most novelists are launched with no support at all. Advertising budgets for first novels are nil. Author tours are reserved for celebrities and experts in baby care or cancer prevention. The situation is little better for most second, third, and fourth novels. Any boost that a developing novelist gets is likely to come from outside sources: good reviews, award nominations, hand-selling in independent bookstores. Publishers do at times contribute to a promising career—those front-of-store displays in chain bookstores do not come cheap—but by and large the fortunes of fiction writers depend upon a certain kind of magic.

It’s becoming a recurring theme of this newsletter that nobody knows if your game/book/song/whatever will pop off, and Donald Maass agrees.

But in the final sentence of the paragraph above, he begins to hint at something mysterious. A certain kind of magic.

What is this magic? In the business, it is called “word of mouth.” In the real world, it is what happens when your friend who reads too much grabs you by the arm, drags you across the bookstore aisle, snatches a novel from the shelf and thrusts it into your hands, urging, “You have got to read this. It’s fantastic.” You sample the first page and, persuaded, get in line to pay.

Word of mouth. When a bookstore clerk who reads too much does it, it is termed “hand-selling.” Whatever the label, it is the power of personal recommendation, the persuasiveness of everyday salesmanship. Word of mouth is the secret grease of publishing. It is the engine that drives breakouts. It must be. What else can explain why breakouts frequently catch publishers by surprise?

But what causes word of mouth?

What causes consumers to get excited about a work of fiction? Reviews? Few see them. Awards or nominations? Most folks are oblivious to them. Covers? Good ones can cause a consumer to lift a book from its shelf, but covers are only wrapping. Classy imprints? When was the last time you purchased a novel because of the logo on the spine? Big advances? Does the public know, let alone care? Agents with clout? Sad to say, that is not a cause of consumer excitement.

I like this: Maass is effectively indicting himself here too. He’s an “agent with clout.” But he admits that his endorsement of books isn’t capable of driving sales.

Instead, Maass observes that when excitement for a book kickstarts real word of mouth growth, it’s "as if a sort of ‘telepathic link’ has connected readers from across the country.”

What is that link?

The link is the author, or rather, the story he has told. Something about it has gripped his readers’ imaginations in a way that his previous novels did not. His characters are in some way more memorable, his themes more profound. For some reason or other, this new novel sings. It matters more. His readers project themselves into the world of the novel and think about it days after its final page has been turned. What is going on? What are the elements that make this new novel so much bigger and better?

That “magic” is whatever Faulkner found in between writing Flags in the Dust and The Sound and the Fury.

Maass goes on, in the ~272 pages that compose Writing the Breakout Novel, to make an impassioned case for true artistic and literary greatness as being the key ingredient in any breakout novel’s success. He gets into the weeds of plot, characterization, and style, while talking a lot of hilarious trash about the publishing industry.7

It’s a fun read even if you have no interest in writing novels, because of how seriously and knowledgeably he writes about the topic. The guy loves novels:

Great novels—ones in which lightning seems to strike on every page—result from their authors’ refusal to settle for being “good.” Great novelists have fine-tuned critical eyes. Perhaps without being aware of it, they are dissatisfied with sentences that are adequate, scenes that merely do the job. They push themselves to find original turns of phrase, extra levels of feeling, unusual depths of character, plots that veer in unexpected directions. They are driven to work on a breakout level all the time. Is that magic?

Not at all. It is aiming high. It is learning the methods and developing a feel for the breakout-level story. It is settling for nothing less.

You can already see the midwit meme template in your mind, can’t you? The cringing author at the center of the bell curve weeps about lack of support from his publisher and the failure of critics to appreciate his genius, while the deformed homunculus and hooded priest on the extreme ends of the IQ distribution sagely whisper: “just write great books.”

The Age of Uncertainty

In the 23 years since Maass published his book, the power of gatekeepers in the world of literary fiction has nearly completed its long collapse.

The gatekeepers aren’t dead yet, as the big five publishers retain control of an enormous part of book distribution. But their power to do anything for books beyond simply running the printing presses is now at an all-time low, a fact evidenced by the spectacular failure of their occasional attempts to artificially pick a winner.

Word of mouth sales, meanwhile, are now more than ever the only engine driving sales for any “breakout” novel, with automated, algorithmic content recommendation systems on social media acting as a sort of accelerant on the natural word of mouth process.

It’s a change that comes with heavy trade-offs. You wouldn’t want novels to be subjected to the brutal gatekeepers Faulkner faced in the 1920s. But are the algorithms really a preferable master?

When the barriers to publishing fell, the structure that once supported and guided young authors crumbled as well. The gatekeepers disappeared, but so did the gates, along with the roads that led to them. The result is a loss of certainty—of the ability to see a path worth following at all.

With no anointed masters to appraise and guide us we’re left on our own, working in the dark and whispering to ourselves:

Just write a great book. Just make a great game.

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go read some more weird old books.

I’ll see you next Friday.

If you pick up Blotner’s Faulkner biography, make sure you get the 1991 single-volume edition. In an amazing act of respect (and probably journalistic malpractice), Blotner waited until well after Mrs. Faulkner had died to produce a second edition of the biography with all of the really juicy stuff about Faulkner’s misdeeds included. Blotner’s New York Times obituary tells that story and is solid promo for the book.

Faulkner spelled words however he pleased, “damdest” being one mild example.

After I graduated from The University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi (Faulkner’s hometown) my first “real” job led me to Culver City, California, where I lived for six years. Ever since reading Blotner’s biography of Faulkner and discovering that odd connection, I’ve felt vaguely haunted by the man.

To support himself, Faulkner had to take a job working in the Ole Miss power plant. He later said that he wrote As I Lay Dying while slacking off on the job, using a flipped-over wheelbarrow as his writing desk.

Compare that figure to the over 17,000 new games released on Steam alone so far this year, and you realize how much crazier things could get for the games industry.

The interest rate data offers another possible parallel between the games industry in 2024 and the book publishing world of June, 2000. (The recent waves of massive layoffs in games were fueled in part by rising interest rates.)

An example of Maass at his sassiest, discussing a common breed of mid-career novelist who is losing their touch but doesn’t know it yet:

It can be alarming to meet certain novelists at writers conferences. I feel a bit like a cardiologist shaking hands with someone who is dangerously overweight. Sure, I think, you may have been on the tennis court this morning, but I can predict, give or take a few months, when you are going to have the Big One: your first heart attack. And looking at you, I am concerned that it might be fatal.

It is not only midlist authors who worry me. Another high-risk group are authors who have gotten blue-sky advances: those mid-six-figure, envy-producing, out-of-nowhere lightning bolts of good fortune that produce feelings of smug security. Have you met this type? Their serenity can be annoying to those who perceive themselves as lower on a ladder. Being on a higher rung, though, means there also can be farther to fall. And fall these types do—far more often than anyone will admit, least of all their high-octane agents.

Sadly, too many novelists phone me, the fiction-career cardiologist, only after the Big One has landed them in the emergency room. The warning signs were all there: declining sales, poor covers, no promotion, indifferent publishers and agents. It was only a matter of time. But still they did not see it coming.

Worst of all, the plainest indications of illness were right there in their novels. After a “promising” debut book, a weak second novel sold through poorly; meaning the unsold copies came back to the publisher by the truckload. Reviews of the next few novels were “mixed.” The fifth book never caught fire, and having been let down by the last few, I did not even buy it. These are novelists who are slipping off my radar screen, and if that is how I feel, it is a sure bet that their publishers, book-store chains and, most especially, their readers already feel exactly the same way.

What a great piece!

This is probably an unpopular opinion, but... I miss gatekeepers. At least a little.

Sure, it's great that artists don't need a gatekeeper to make it big now, but at the same time, there's just so much STUFF out there these days, whether it be books, movies, shows, or games, and most of it is mediocre to terrible. Even the good-to-great stuff can be hard to find unless it's universally praised (word of mouth again), and even then, that doesn't guarantee an audience. Perhaps it's always been this way, but I feel like the sheer glut of product brought on by lack of gatekeepers has been detrimental. No, the gatekeepers weren't always right, but they could by and large keep out lesser works of artists from being released into the atmosphere.

Thanks, Ryan!

Will definitely be picking up the Blotner biography. Thanks for sharing! I came for the video games, I stayed for the Serious Literary Discussion.