The Strange Descent of the Cozy Farming Sim

On the ways game genres evolve and continue to bear fruit

I’ve been traveling a lot for work, and my go-to airplane game of late has been Fields of Mistria, a sort of fantasy-inspired take on Stardew Valley which itself was inspired by a whole lineage of farming games that came before it.

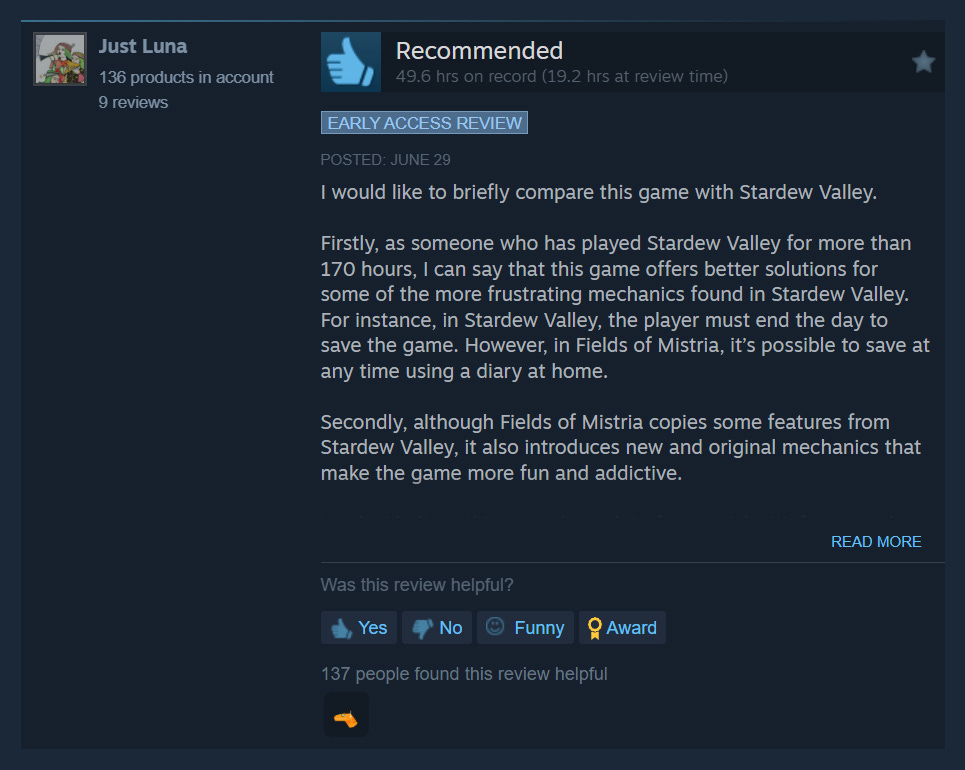

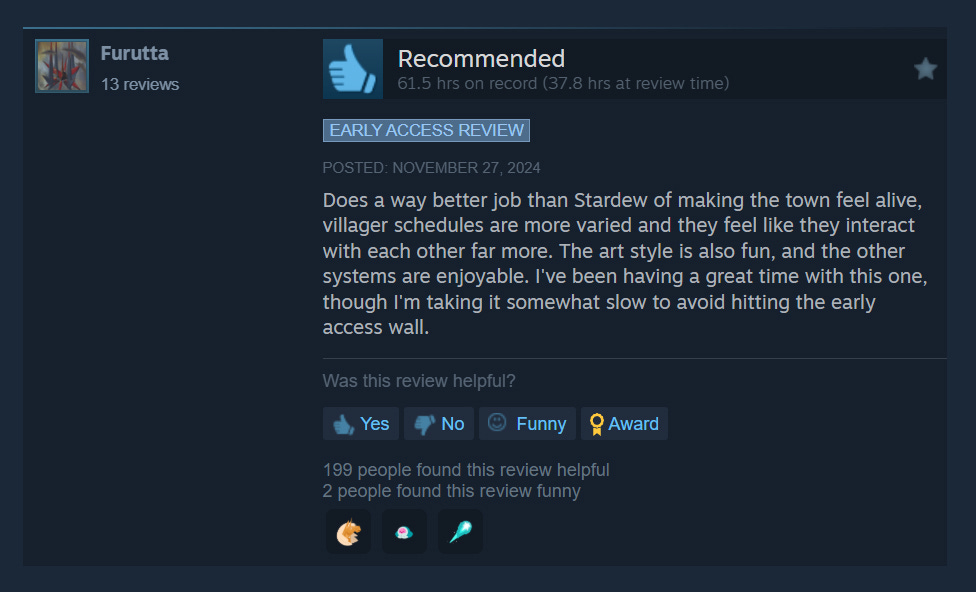

If you read the 17,000 “overwhelmingly positive” English reviews for Mistria on Steam, one thing jumps out: everyone intuitively understand that this game exists explicitly in relation to Stardew Valley. Reviewers praise it for fixing the Stardew’s problems, as if it were a patch for the game rather than a standalone artistic work.

Even Mistria’s creative distinctions—reviewers often praise the writing and characters—are complimented specifically in reference to those same elements in Stardew.

The other big difference, according to Steam reviewers, is that Mistria’s villagers are hot.

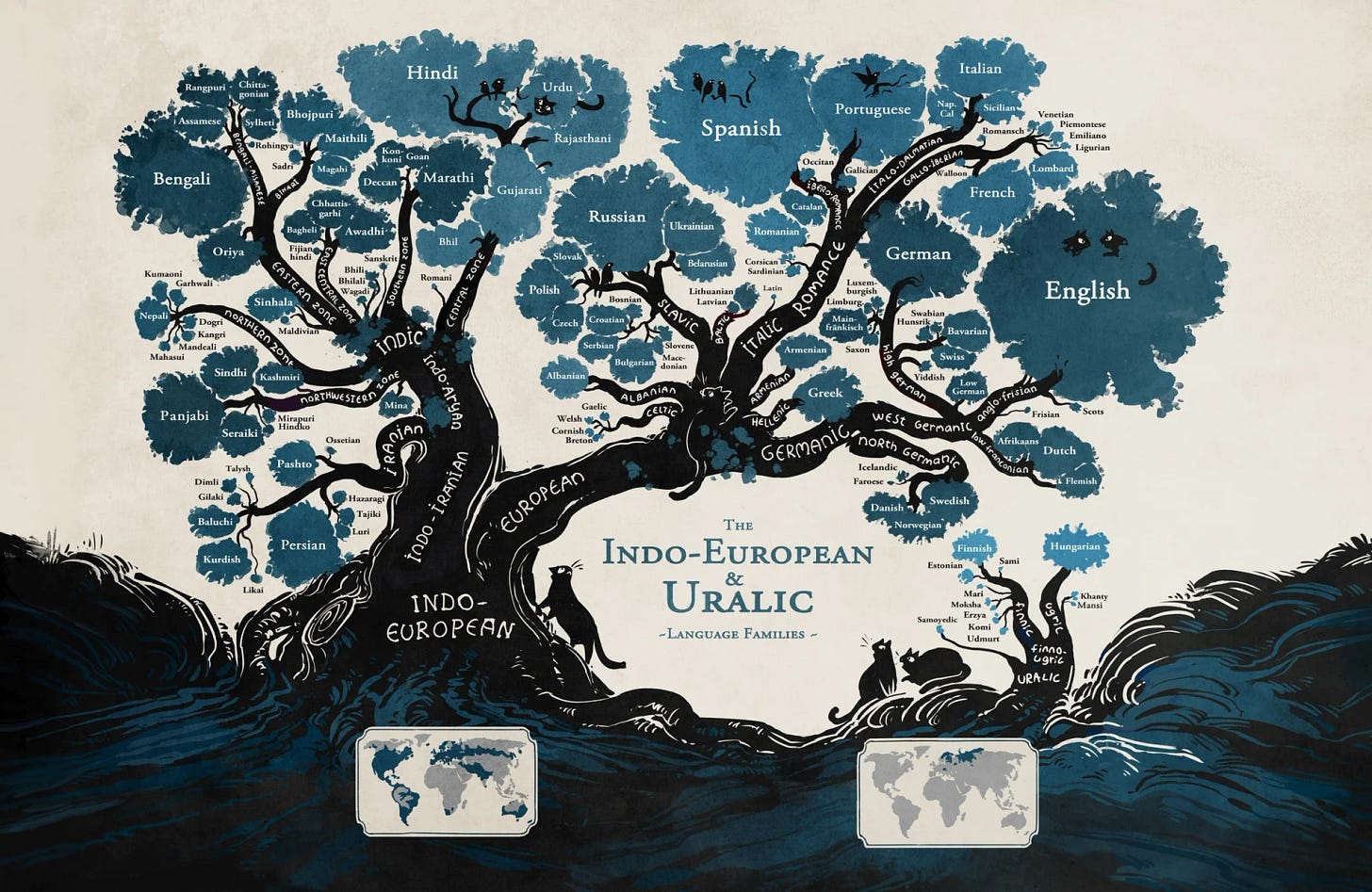

I’ve been thinking about the ways game genres evolve—about the tendency for beloved works to spawn branches bearing new fruit. It reminds me of this beautiful language family map (see up top) made by the Finnish graphic artist Minna Sundberg, which illustrates all the unexpected connections between various Indo-European languages.

You could probably draw a similar tree-like visualization to explain the history of many evolving fields of production, whether cars, recipes, or paintings. I don’t know if the metaphor holds for all art forms, but the image of a tree works particularly well when tracing the evolution of certain game genres, especially the “cozy farming simulator.”

Roots

In soil fertilized with ideas from PC classics like Little Computer People (1985) and SimFarm (1993), the base of the cozy farming sim tree is undeniably Harvest Moon (1996), a Super Nintendo game that went on to produce over 30 sequels and spin-offs—and which despite some licensing rights shenanigans continue to release today as entries in the Story of Seasons series.

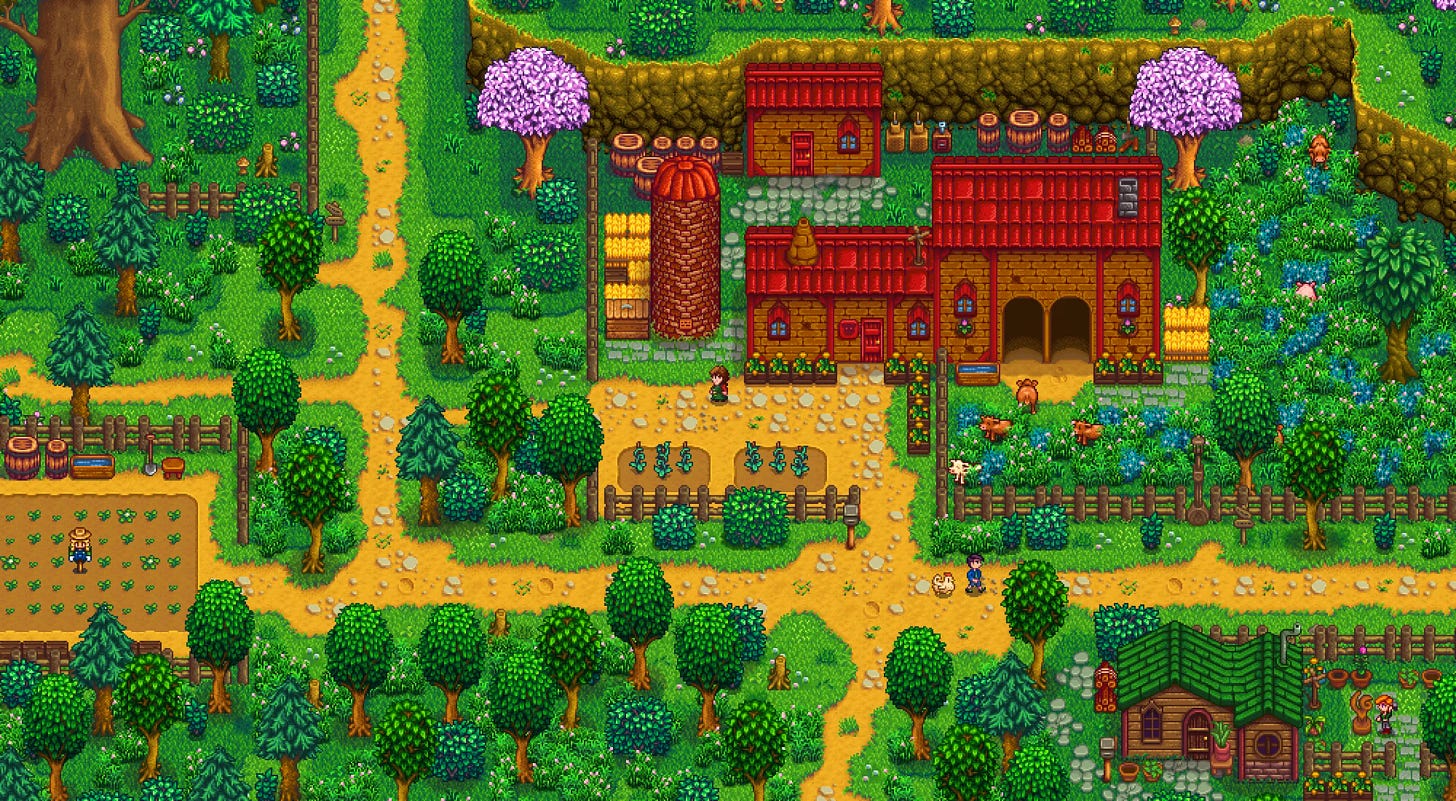

From this trunk, countless fecund branches have sprouted, some you might call “cozy” (Animal Crossing, Palia) and some decidedly more gritty and capitalistic (FarmVille, Grow A Garden). But the biggest and most abundant branch of the tree is without question Stardew Valley (2016), originally created by Eric Barone. As of December of last year, it has sold over 41 million copies1 across all platforms, making it one of the best-selling independent games ever made.

Trunk

Barone’s story is by now well-known, and he was always forthright about his inspirations. “My whole reason for making Stardew Valley was to eventually add all the things that I wished Harvest Moon did,” Barone wrote in a Reddit thread posted in 2012, years before the game released.

The language used here is interesting. He wasn’t making something merely “like” Harvest Moon; his vision was to preserve that game’s core while adding more, modifying the base and extending it in new directions. Over the years people have used different words to describe the relationship between Stardew and Harvest Moon. Is it an homage? A spiritual successor? Some cynics have even used the word clone. I’d argue that none of these capture the real nature of the relationship between the two games, which is more like familial descent. As an approach to artistic creation, there is something like the mindset of a modder here.

Branches

There are many reasons to mod a game. You might be “fixing” something annoying or problematic with its design, or adding components that feel missing, or customizing the experience in ways desired only by you. The modder respects the original vision of the artist, while imagining that the addition of their own creative touch might result in something even better.

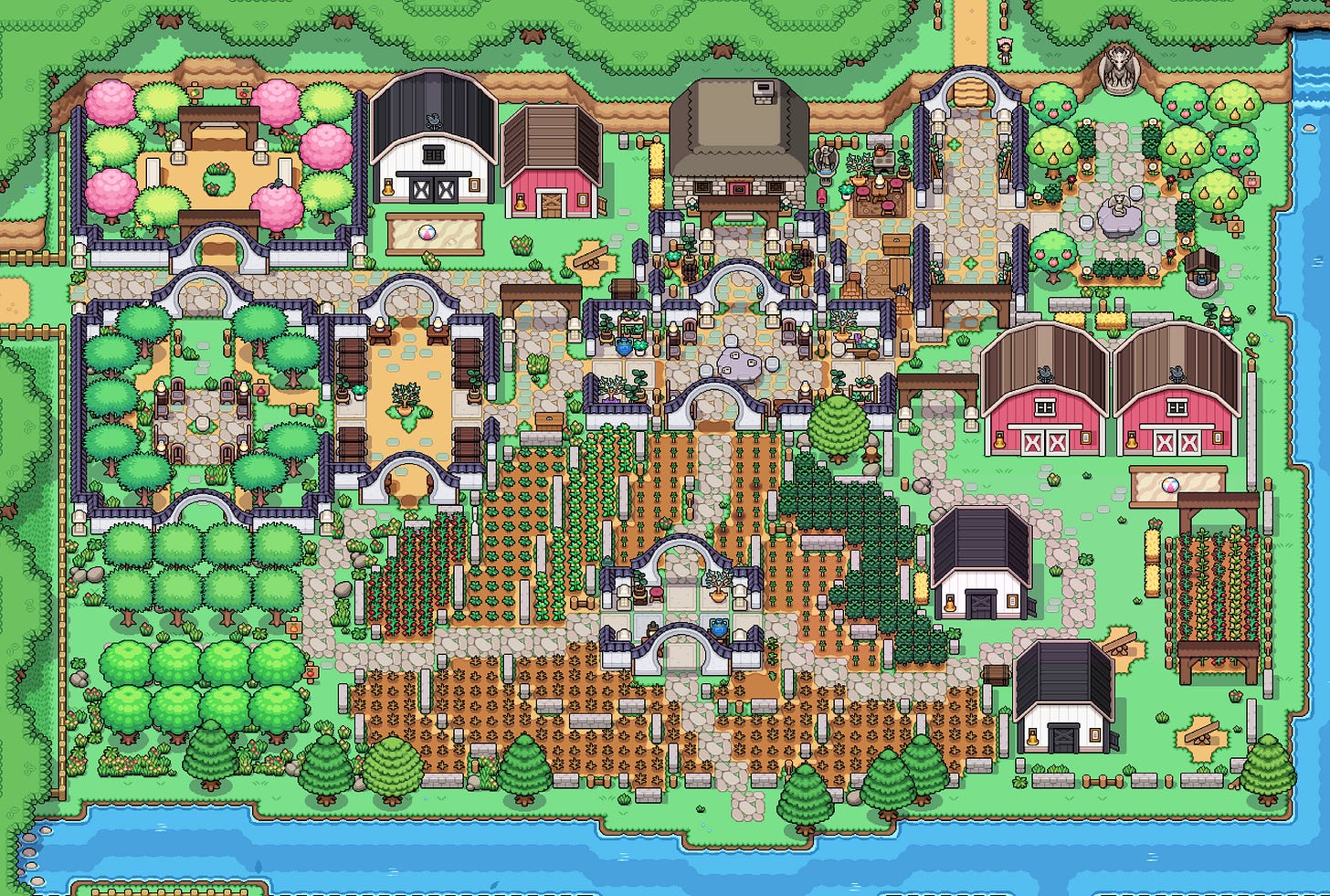

And so of course, even after Barone delivered on his vision of a game with “all the things he wished Harvest Moon did,” others imagined even more ways to add on. The most popular mod for Stardew Valley is called Stardew Valley Extended, which adds new characters, areas, items, among countless other tweaks to the game’s design. It has been downloaded over 20 million times on Nexus Mods.

At some point Extended’s creator, FlashShifter, had his car stolen and, in a fit of desperation, reached out to Barone and asked if he’d be willing to pay him for work.2 Barone hired him, and Flash wound up becoming an actual developer on Stardew Valley itself. He even contributed meaningfully to the game’s massively popular 1.6 update—a rare example of a trunk re-absorbing one of its branches.

Fruit

In professional games studios, concept artists often leverage direct references to other works—especially via mood boards—when creating new characters or worlds. I’ve heard it said more than once, by artists working in these roles, that the mark of good work is in how well one “hides your references.” This always struck me as funny, as if the artist is a furtive little trickster using misdirection to sneak their inspirations under the audience’s nose.

That’s one way of making things, I suppose. But maybe equally as valid is an approach where the creator hides nothing, showing all their references right out in the open, while managing to produce something new and beautiful all the same.

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go see if my wife needs any help in the garden.

Source: https://www.stardewvalley.net/press/

This was all revealed only recently, in an interview FlashShifter did with the admins of Nexus Mods earlier this year.

The spirit of "build a better mousetrap" still thrives in the games industry! I've played several cool romhacks from r/PokemonROMhacks, this series feels ripe for "branching" but the logistics of making a collection of hundreds of cool monsters to trade and battle with is tough for most small developers.

Especially interesting take in light of Nintendo's recent assertion in legal proceedings that, "Mods are not games..." https://www.ign.com/articles/nintendo-says-mods-dont-count-as-prior-art-as-theyre-not-full-games-attempting-to-sway-judge-in-palworld-lawsuit One wonders how to square this against, say, CS:GO or [insert any mod that's clearly a game here].

My own favorite "family tree" is the Quake engine one. This is, in my not-so-humble opinion, the most important family tree in all of gaming. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quake_engine

Also reminds me of *possibly* the most important family tree in software - Unix's. Which of course gave us Linux which of course has its own incredibly thick and healthy family tree.

Really interesting when individual studios go full family tree style themselves. Apex is set in the "Titanfall universe" (what that exactly means is certainly open for debate...), but I think of it most clearly as a branch on the family tree. It couldn't exist without Titanfall. So it's clearly derivative art. But also distinct. And, clearly, was designed in large part to address some of the shortcomings/flaws - at least from the multiplayer perspective - with Titanfall (2). I think derivative art is fascinating. More so even than straight sequels, because I think you have a cleaner slate to start from and you're less bound by the need (perceived or real) to try to create some sort of continuity with the previous installment.