Valve's 30% Platform Tax is Bad for Small Developers

It's time to follow Epic's lead by offering 0% fees on each dev's first $1 million.

You’ve already seen the news about the Epic Games vs. Apple court battle. Years into Epic’s war against the App Store’s 30% fee on purchases, the Fortnite maker squad-wiped Tim Cook and crew. All US-based developers can now link out to their own storefronts from within iOS apps, avoiding Apple’s platform tax entirely.

As soon as the ruling came through, devs took advantage. Spotify is selling audiobooks through its app now—without cutting in Apple. Amazon added a similar link-out option to sell Kindle books. And Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney has gone on a victory tour, especially after Apple allowed Fortnite to return to the App Store. Meanwhile, European regulators look poised to force similar changes in their market. For Apple, it seems, the beatings will continue until morale improves.

So Sweeney got his long-sought victory royale against Apple. But that reminds me of another fight—also over 30% fees—that Sweeney picked eight years ago.

This time it was with Valve.

Exactly 27 days after the initial release of Fortnite, Spicy Tim posted the following:

Our boy Timmy Tweets was taking open shots at his industry peers in Bellevue.

This did not go unnoticed. About two hours later, Valve founder and CEO Gabe Newell shot Sweeney an email: Anything we doing to annoy you?

Who is Sean Jenkins? I don’t know, and neither did Timbo.1

Always one for a PvP match, Sweeney replied to Newell:

This is spicy stuff. I mean, our guy was basically calling Valve a bunch of rentiers. He says they could be taking as low as 7% instead of 30%. But what exactly were Gabriel and his Gallant Gamers supposed to do here? Give up billions in revenue just because the Fortnite dude pushed them around?

That’d be ridiculous. Right?

Well. One year later that’s exactly what happened.

In November of 2018, Sweeney emailed the Valve team again to give them a heads-up about his plans to launch the Epic Games Store:

The rest of the email goes on to share Sweeney’s master plan to put pressure on Apple to open up its App Store ecosystem. “A timely move by Valve to improve Steam economics for all developers would make a great difference in all of this,” Sweeney wrote.

Four days later, Valve made a timely move—but it wouldn’t be for the benefit of all developers.

Frightened by the prospect of the biggest AAA third-party devs abandoning Steam for Epic’s new offering en masse, Valve announced a new, bizarrely regressive fee system. Developers on Steam would continue to pay 30% of gross revenue on their first $10 million earned as a fee to Valve. But revenue over $10m would be charged a 25% fee, and revenue over $50m would enjoy a mere 20% fee.

It was an obviously opportunistic move. Valve would continue to take 30 cents on every dollar made by the little guys, but it would make concessions to the big dogs. Stick with us, make your millions, and we’ll give you a deal just good enough that you won’t be tempted to abandon Steam and migrate over to Trader Tim’s.

Sweeney was enraged.

So Tim was pissed that Valve didn’t lower fees for all developers, but the drop from 30% to 20% take on revenue after $50m was still significant.

I asked games industry analyst Matthew Ball about this, and he pointed to the scale of the change: “This substantially reduced EGS's commission-specific appeal but has sent billions in more revenue to developers,” Ball said.

Mostly, of course, the savings have gone to big established developers like KRAFTON’s PUBG (an estimated $4.5 billion grossed on Steam),2 or EA’s Apex Legends (est. $1.4 billion Steam gross) or Bungie’s Destiny 2 (est. $870 million Steam gross). But some small devs benefited too. The one-man hit Stardew Valley is estimated to have grossed over $250 million on Steam alone, for example. Eric Barone might still be known as ConcernedApe, but the man has nothing to worry about. He’s on that juicy big boy 20% plan, and has been for a long time.

In other words, Valve responded to the threat of competition by voluntarily taking a big financial hit. Crazy how competition can force change, right?

Sidebar: The Origins of the 30% Fee

The precedent for the now industry-standard 30% platform fee for digitally-distributed games is sometimes said to have originated with Xbox Live Arcade.3 In a 2016 interview with IGN, former Xbox executive Greg Canessa said “We had no idea that little meeting we had was the rev-share archetype for the next ten years of downloadable software.”

But by XBLA’s launch in 2004, iTunes had already established the 70/30 split a few years earlier—and you could argue that this model had even further precedent going as far back as the 1970s, when Warner Bros. charged a 30% distribution fee for VHS tapes.

The 30% standard cut was solidified by the late 2000s with the adoption of the 70/30 model by both the App Store and Google Play. All three major game consoles adopted the 70/30 split for their digital storefronts as well, with the logic being that Nintendo, PlayStation, and Xbox would use the fees to recoup the cost of distributing not just the software from third party devs, but the hardware as well.The 70/30 split was starting to show cracks by the late 2010s, when Valve adopted its 20% standard for high-earning games. Other exceptions followed. In 2020 Apple lowered its App Store take to 15% for small businesses earning under $1 million. And in 2021 Microsoft followed Epic’s lead and adopted an 88/12 split on the PC Microsoft Store. After Epic’s recent courtroom victory against Apple, the future of the 70/30 split looks shaky almost everywhere.

The one place the 70/30 standard will probably hang on the longest is in the console business, where the platform makers often sell hardware at a loss in the hopes of making up the difference later with a combination of first-party software sales and platform fees.

But let’s put a pin in that for a moment and continue on with our story.

True to his word, on December 4th of 2018, Sweeney revealed his plans for the Epic Games Store, and on December 6th it went live. “Our goal is to bring you great games, and to give game developers a better deal,” the official launch blog said. “They receive 88% of the money you spend, versus only 70% elsewhere. This helps developers succeed and make more of the games you love.”

The response from players? Mostly annoyance.

See, players actually like using Steam, and they don’t care how much money developers have to give to Valve. And who can blame them? Steam is great! Many players have built up massive libraries over the course of a decade there, with no small help from Valve’s regular “Steam Sales,” where the company hauls in 3rd party devs and encourages them to sell their wares on massive discount.

Plus, the Epic Games Store was missing features. There was no shopping cart! It was laggy. Buggy. And over the coming months and years, a lot of Steam devotees became particularly incensed at Epic’s strategy of paying developers to release their games on the EGS as a timed exclusive. Gamers didn’t care whether Epic was giving devs a better deal if it caused inconvenience to the end user.

In the end, the Epic Games Store didn’t make much of a dent in Steam’s market share anyway. Simon Carless from GameDiscoverCo told me he estimates that Valve earned $14.1 billion from Steam in 2024. Meanwhile, Epic reported just $1.09 billion in total player spending on the Epic Games Store in 2024 (including Epic’s own games). Of that figure, $255 million was spent on third party apps using Epic Payments—an 18% drop from 2023. If Epic only collected 12% of that spend as fees, it would only have made $30.6 million on 3rd party game spending.4

In other words: Valve isn’t facing serious competition from the Epic Games Store.

Many will see these statistics and blame Epic for failing to deliver a better product. Steam’s better, so it won. End of story. There’s something to that—you can’t dismiss the quality of Steam. But consider the counterfactual: Did EGS ever really have much of a shot at success, even if it had managed to achieve perfect feature parity with Steam? Steam launched 22 years ago, so many users have spent over a decade adding games to their Steam libraries. What would it take for these people to switch their buying habits to a different platform?

“It’s easy to understate the potency of Steam's entitlements lock-in (game ownership, achievements, player networks),” Matthew Ball told me. “It's effectively impossible for a long-time user of Steam to 'leave' Steam.” Rather, they’re at most going to start also using another store.

So here’s the situation:

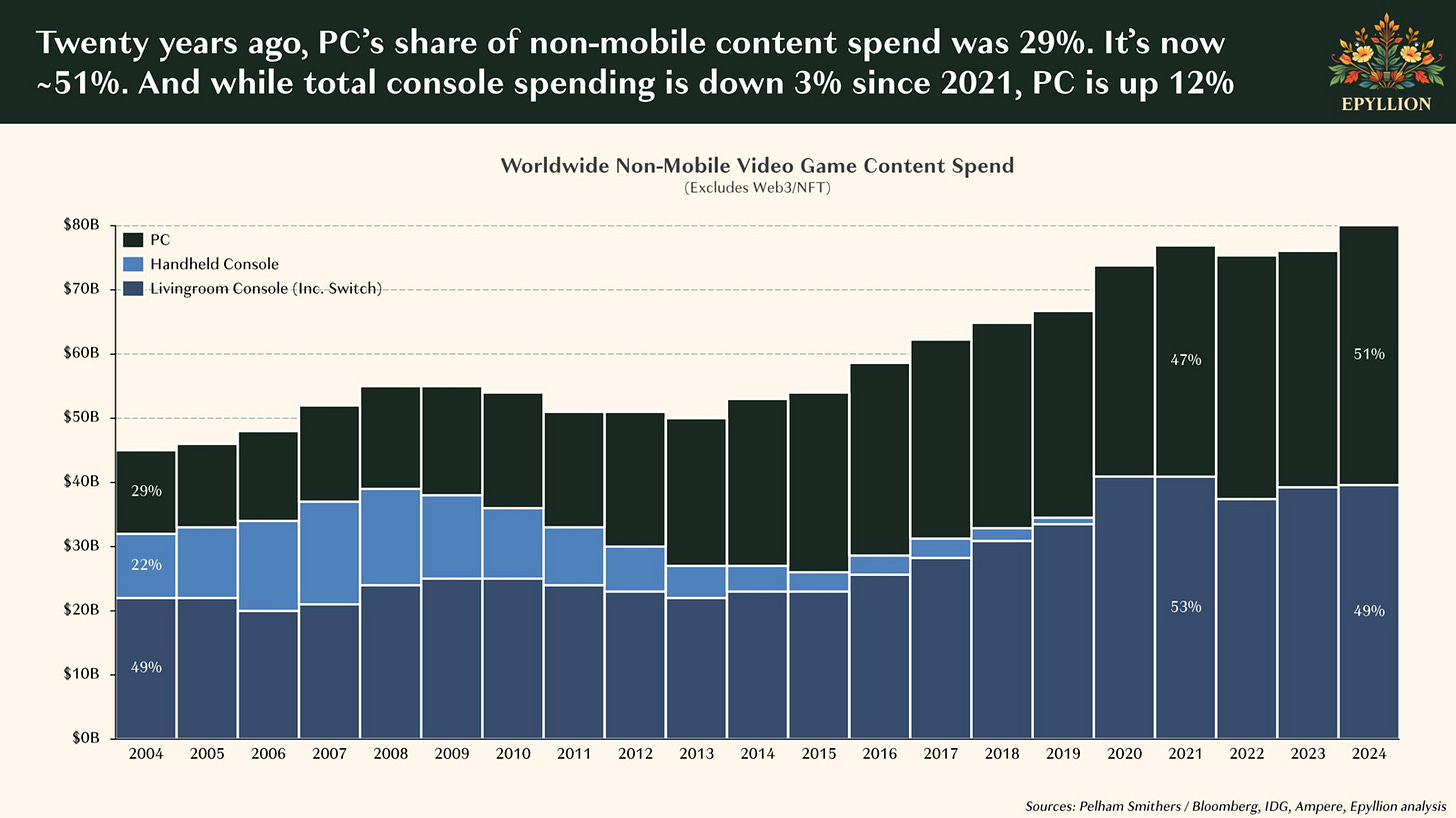

Valve dominates the PC games market, at least for third-party storefronts

The audience for Steam is locked in, both because of the quality of the product and the long-term advantages Valve wisely built

So every independent developer on PC is effectively forced to publish on Steam and fork over 30 cents on every dollar made to Valve

I don’t think “monopoly” is the right word to describe this situation—though that argument is currently being debated by the parties in Wolfire v. Valve, the ongoing court case which brought us the leaked emails shared earlier in this article. But EGS, Itch.io, and GoG do exist. Game Pass for PC is doing its thing. So I’m skeptical a judge is going to find that Valve did anything wrong to achieve its dominant position. They won fair-and-square.

So what word should we use to describe this situation? There’s something novel happening in the platform era, where one or two privately-owned companies accrue such massive distribution advantages that they’re able to dictate the terms of business for a meaningful chunk of entire industries. We’ve seen it with mobile storefronts, with ebooks, with music streaming. The 16th century concept of “monopoly” doesn’t capture the nuances. Nonetheless, something smells funny about this tendency of 21st century digital platforms to resist competitive pressure—and both courts and legislators are starting catch on.

Here’s one thing we can say for sure: If the Valve was facing competition, we’d see them making more concessions to developers, like Epic’s recently announced plan to take no cut on third-party developers’ first $1 million earned in annual per-game revenue. We’ve seen the Bellevue Boys make some concessions before, like when they were trying to head off the threat of competition from the Sweeney Squad. But that threat never materialized. So Valve is set to continue taking a near 1/3rd slice of the money earned for almost every commercially viable indie game published on PC.

This despite the fact that 85% of sales on Steam come from the top 50 games each year:

Why are the creators of the 18,950 smallest titles on Steam forced to pay up at the highest rate (30%), when they account for less than 15% of total spending on the platform? When a government charges higher tax rates to the lowest earners, we call this regressive taxation. When a private company does it, we shrug and say “it is what it is.”

The result is an unnecessary burden on developers that may be in the most precarious financial situations.

To illustrate, imagine a small team of five game developers. They work together for two years to create a game that—miracle of miracles—manages to gross $1 million. This is an amazing feat, something very few games achieve each year on Steam. But what would they actually take home?

First, Valve would take $300k, right off the top. Across five devs, you’d have $700k remaining. Not bad! That’s $140k each. But it took two years to make the game. So your annualized salary is more like $70k, less than an entry-level salary at a mid-size game studio. And that’s before taxes, and—in America—the cost of health care. And what about cost of equipment? Marketing spend? Publisher fees?

You make a million-dollar game, and walk away with less than the assistant manager of the car wash at Buc-ee’s.5 Meanwhile, Valve is pocketing a C-suite salary.

Right now, this is simply the deal you get as a small developer on Steam. And if you want to reach players, you will accept the deal. It is what it is.

But is it good for small developers? Valve is undeniably one of the greatest game companies in the world when it comes to delivering value for players. I would even argue they don’t get enough credit for some of the player-friendly choices they make.6 But with more developers than ever opting into the garage-band game economy Steam has helped to enable, what responsibility does Valve have toward these creators?

For now, Valve has all the say. Gabe could take the initiative to give small developers a better deal.

If they don’t, the next chapter of this story might be written by the courts.

That’s it for this week.

I’m gonna go fuel up at my local Buc-ee’s.

The guy’s name is actually Sean Jenkin (no “s”). At the time, Jenkin was a Valve employee that had caused a minor uproar earlier that day with a forum post about policies regarding Steam key distribution. That isn’t really relevant to this story, but it is extremely funny how quickly Gabe was willing to throw an employee under the bus—while misspelling his name.

This and all following revenue estimates come from GameDiscoverCo Plus, which is worth paying for.

UPDATE: Matthew Ball reached out to share evidence that the 30% standard cut can be traced back to the original Pac-Man.

From his book:

In 1983, the arcade manufacturer Namco approached Nintendo about publishing versions of its titles, such as Pac-Man, on its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). At the time, the NES was not intended to be a platform. Instead, it played only titles made by Nintendo. Eventually, Namco agreed to pay Nintendo a 10% licensing fee on all of its titles that appeared for NES (Nintendo would have right of approval over every individual title), plus another 20% for Nintendo to manufacture Namco’s game cartridges. This 30% fee ultimately became an industry standard, replicated by the likes of Atari, Sega, and PlayStation.

Forty years later, few people play Pac-Man anymore, and costly cartridges have transformed into low-cost digital discs manufactured by game makers and even lower-cost bandwidth for digital downloads (where the costs are mostly borne by consumers via internet fees and console hard drives). Meanwhile, the 30% standard has endured and expanded to all in-game purchases, such as an extra life, digital backpack, premium pass, subscription, update, and more (this fee also covers the two to three percentage points charged by an underlying payment rail, such as PayPal or Visa).

—Matthew Ball, The Metaverse: Building the Spatial Internet (Fully Revised and Updated Edition), 2024

Assuming all $255 million was subject to Epic’s normal 88/12 revenue split

Top of the range pay for a car wash assistant manager at Buc-ee’s is $33/hr.

Probably very few Steam users realize that developers cannot pay Valve for promotion on Steam. Unlike storefronts on PlayStation, Xbox, Apple, or Google, Valve simply won’t let you buy ad slots, presumably because they don’t want to compromise the player experience. This is a company that cares about its users.

Man, what a good read this was, great work Ryan. It is interesting to start seeing some *hard-to-see-but-definitely-there* cracks on Steam's impenetrable defense throughout the years.

Yes, Steam has done A LOT for gamers around the globe, and they have earned their position at the very top of the market by virtue of arriving first and managing to defend their position while being very consumer friendly. But there are things that could improve, things that most are willing to let slide due to convenience, and its a good thing to finally star having a discussion about it.

The concept of monopoly you brought up is something I have thought about so much already.

While I agree that it is in Steam's merit that they were able to build such a well-rounded product, it reached a point at which they became renters and are doing more harm than good, and the way they shook policies around to support the big guys rather than the other way around point out they're trying to stall (such as Apple did through their process) rather than solve for it.

And while I think Epic is doing god's work by suing Apple and trying to "right" this, they only targeted EGS at developers, failing to understand that this gtm was supposed to be focused on the end consumer and have sprinkles towards developers rather than the other way around put them at this awkward position.

The platform itself is evolving, but still lags so much behind Steam and tbh I think it's as much about community (friends list, reviews, groups, playtime counter, friends also played, and so many other features built through decades) as it is about sunk cost fallacy (games library)

great read, Rigney!