Can We Please Just Be Normal About AI

On world models and the temptation to view new things through a well-worn lens

When I talk privately with game devs and industry people, more and more of them admit to feeling exhausted by the way AI gets discussed online, especially in games enthusiast and industry circles.

One problem is that voices representing the most extreme worldviews tend to dominate the conversation. The stories told about AI's looming impact on games tend to reduce down into one of the following visions:

We are building God (and also The Matrix) inside a datacenter in Milwaukee

or

Machines that feast on stolen art are drying up the oceans, and the only source of water left on Earth will be the tears of unemployed former game developers.

Neither of these visions have much to do with observable reality.1 And the more tightly people clings to one of these visions, the more difficulty they have in understanding and reacting reasonably to novel applications of AI tech.

Far and away the clearest example of this as it applies to games has been the recent emergence of “world models,” basically a new form of interactive video where individual video frames are generated dynamically in response to user inputs.

The first, most rudimentary version of these models appeared last year with Google’s GameNGen prototype (built around Doom). This was quickly followed by other AI-generated world models based on other games, like Etched and Decart’s Oasis, a hallucinatory AI simulation of Minecraft that was made playable to the public as a browser app.

Approached on their own terms, these were early demos of a technology with uncertain—but definitely interesting—possibilities.

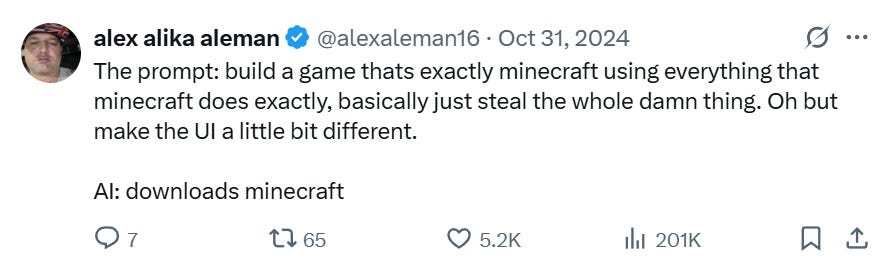

But that’s not how many saw them. Here’s one especially confused reaction to the Oasis demo:

This is a person who is fundamentally missing the point. A demo like this is attempting to show what interactive entertainment might be like on computers that are probabilistic instead of deterministic. It’s not about literally making a new way to play Minecraft. The point is to inspire people to imagine: Wow, what if they developed this model further and trained it on things in addition to Minecraft?

But Alex thought he was looking at just another Minecraft clone. If you’re operating with a broken worldview of what AI is, you actually can’t understand what you’re looking at.

Here’s another example, this time with a person reacting to a similar world model tech demo from Microsoft that happened to be based on Quake II:

There’s a lot to unpack here. Is the idea that this tech is going to harm the developers of Quake II? The reaction only makes sense if you’re predisposed to view every new AI tool as de facto harmful to artists and developers.

In any case, at least one person disagreed with Ruby Ranger's take here: the actual lead developer of Quake II, John Carmack:

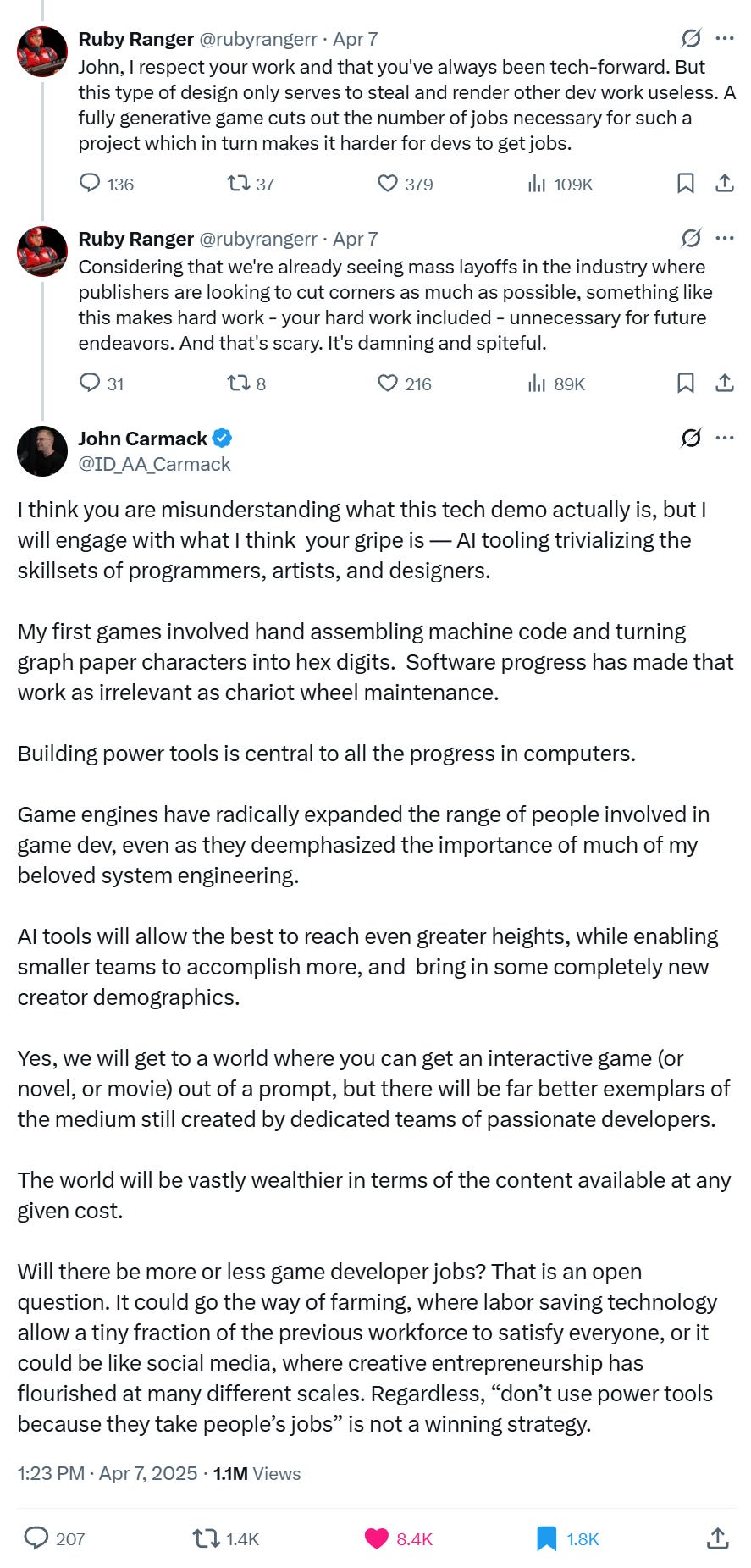

Any person with a shred of curiosity ought to be gobsmacked by an interaction like this. One of history’s most famous games programmers just replied to your sassy tweet to disagree with you. How might you respond?

Instead of asking why Carmack thinks the demo is impressive, the poster took it as a chance to explain to the creator of Doom why he’s wrong. This in turn prompted Carmack to write a thoughtful take on AI tool development and its likely impact on games:

Carmack is introducing a completely different vision for analyzing AI models: not as a uniquely evil or godlike type of computer, but as just another tool. In this case specifically, Carmack sees a demo that fits into a long tradition of software “power tools” that includes ones he himself invented.

You can disagree with Carmack’s take, but let’s adopt his model for a second. There’s a lot to be said for the idea of treating individual AI applications as just another power tool for devs. Slowly, surely, specific AI tools are emerging now that can do things like generate 3D character models from concept art, automatically detect joints for rigging, and speed up the animation process by interpolating frames when given a starting and ending point. Future versions of these apps will make game development faster and easier, but they're hardly set to make human creatives obsolete. To make really high-quality stuff using these tools, they need to be wielded by skilled human operators. And in many cases these tools aren’t even replacing legacy game dev software like Blender. They’re integrating directly with existing tech stacks—just one more tool in the toolbox for artists.

Certainly, many devs say that AI coding tools are dropping their costs and dev time now, and that stuff should only get better. But as it stands today, even AI power-users say that today’s AI tools aren’t good enough to build high-quality games—at least not yet.

One more model couldn’t hurt

I like the way Carmack thinks about AI, but I don’t want to make the case that he’s definitively, 100% correct. The point is that there are other ways of viewing AI, even if you add the “it’s all just tools” model to your toolbox.

Even that way of thinking is inadequate to describe some of the things that are beginning to be achieved with new foundational types of AI, especially the most cutting edge stuff happening in the world model space. If you haven’t already, you really need to watch this demo of Genie 3, Google DeepMind’s new world model:

This, of course, is the same core technology that powered the earlier experiments with Doom, Minecraft, and Quake II… except much more advanced. And it happened very quickly: less than a year after the publication of Google’s GameNGen paper. In fact, the connections go deeper than that. Last week I had a chance to chat with Genie 3 co-lead Jack Parker-Holder for the a16z speedrun newsletter, and he stressed that one big unlock for Genie 3’s advances came from his team’s collab with Shlomi Fruchter, one of the co-authors of the GameNGen paper.

Whatever you call this new branch of the AI tech tree, “interactive video” or “world models,” it’s obviously something different. And yet, this is the cynical, incurious way the only major video game site to cover Genie 3 framed it:

We are suffering from a dearth of imagination, or maybe just a lack of adequate mental frameworks to make sense of this stuff. Truly new things like world models are not AI Gods, or Art Regurgitators, or even Just Another Tool. They are something new. And when we encounter something that doesn’t fit neatly within our existing worldviews—our models for understanding reality—we have to attempt, in a spirit of curiosity, to understand that thing on its own terms.

Above: A Genie 3 “world” generated by Google DeepMind researcher Philip J. Ball

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go play Quake II.

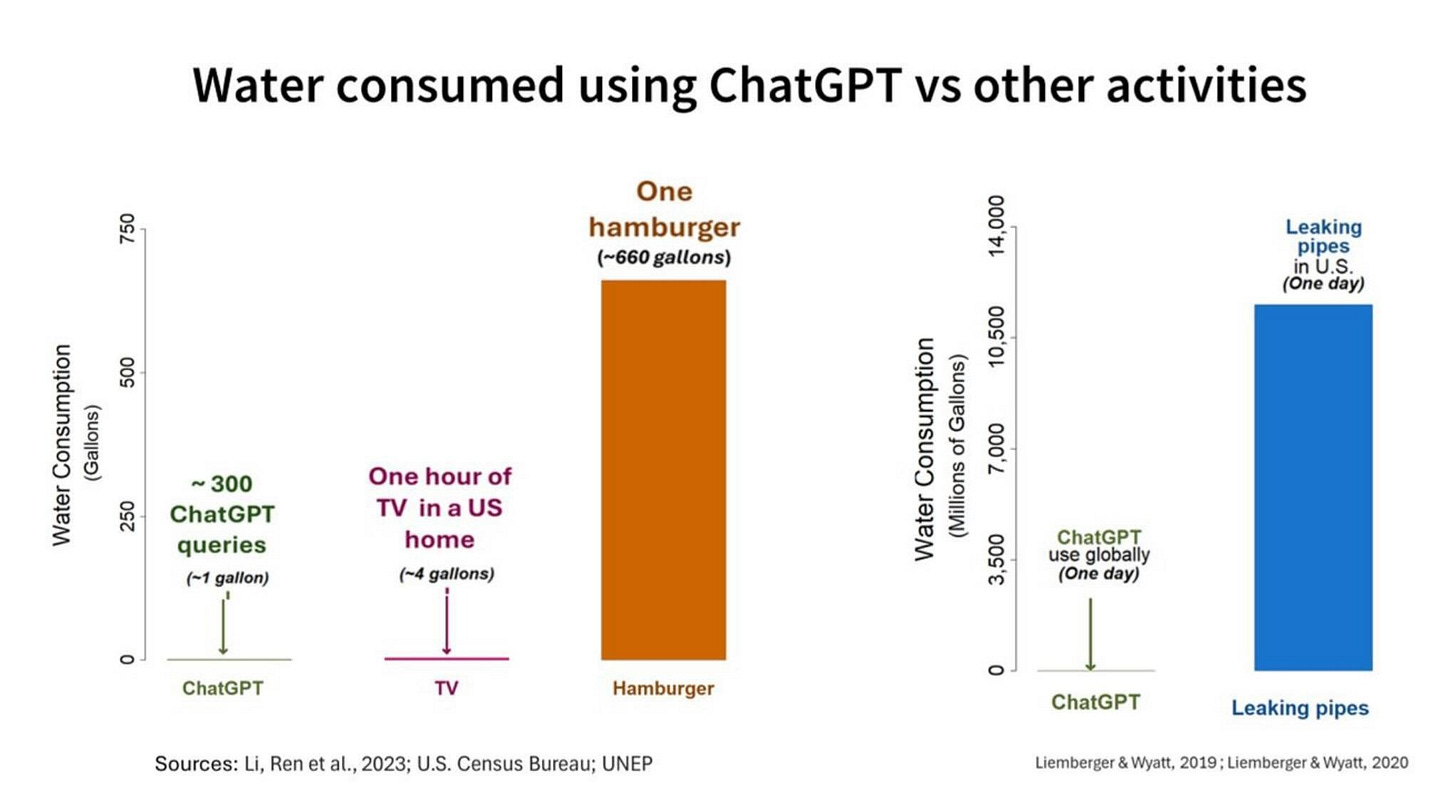

Recent data shows that concerns about AI’s impact on the environment are pretty seriously overblown—especially when comparing AI usage with everyday activities like eating hamburgers, heating your home, or taking showers. University of Oxford Senior Researcher Hannah Ritchie has done multiple excellent deep dives on LLM electricity usage and likely impacts on carbon emissions which are worth reading.

I had an at-least-for-me-interesting interaction with Tom Spencer-Smith on linkedin. You MIGHT remember Tom who was a contractor for Respawn when you were still there (cries inside) who did thin-client development. Basically, how can we automate more of our testing, especially of gameplay, to find the sort of weird edge cases that are the result of sheer volume. He's pretty much all in on AI and on things that are, in many ways, "generic." I.e., he likes unreal because it's very generic which is also why I don't really like it, because it's generic. I think we view unreal the same way, just with him thinking it's good and me thinking it's not good, though in both cases "good" applies to our own specific use-cases. i.e., I am glad unreal exists, but i am also glad i don't work on a game built on top of it.

anyway, re: AI, he said something kind of akin to Carmack, but much more specific and prescriptive in terms of how to actually write code that AI could then 1) understand and 2) expand upon. Basically, he argued, "write a lot of small functions" because AI is better at understanding things the more discrete they are.

And my response to this is basically, "so, treat it like a compiler."

Which I thought was, patting myself on the back, somewhat insightful. And I think that's really what Carmack is saying. He started out literally writing assembly language. That's now been made obsolete by modern high level languages.

And AI is *potentially* just like this. AI is to Python what Python is to C++ and what C++ is to x86 assembly. This is always what gets me about C++ developers who can be a bit (quite) snooty because they are *closer* to the bare metal than a python or javascript developer. This was most definitely a real thing at respawn. Which is not to trivialize the importance of actually understanding what is happening on the bare metal, or that somehow the various depth of a level of abstraction is irrelevant. It isn't. But like, it's also weird. I don't see the same kind of gatekeeping in other areas, though admittedly I don't know what I don't know. But I can't imagine a linguist taking Faulkner to task because he doesn't understand the actual way in which humans learn and process language. That doesn't diminish his writing. And likewise, I can't imagine a neuroscientist saying that the work of a linguist or a writer is somehow less valuable because they don't understand how language actually makes its way along synapses.

Last thought - per Carmack's "...don't use power tools..." is on the luddites and what they actually believed. They weren't, as commonly depicted, anti-tech. They were pro-worker's rights. I.e., what they objected to was that the machines were unsafe. And I suspect that's where the real discussion is to be had but it's currently wrapped too much in doomerism. Some of that is, IMO, justified here because of the way these models were "trained." I think the training of these models is an important part of the discussion and you see this in the big court cases where OpenAI and others are like, "we had to use copyrighted information." And I think that is new. I don't know if we've ever had a new technology that has been so reliant on *involuntary* use of other people's work. And I think that's a big part of why we can't have more nuanced discussion here. And, to me, it is the closest analog we have to the luddite's objections around safety.

THANK YOU. The discourse around AI in gaming is frustrating and exhausting to no end. I hate how the most extreme, unhinged, and self-righteous voices utterly dominate the discussion. The backlash over The Alters and Expedition 33 was frankly ridiculous. It’s unnuanced, uninformed, mob mentality and reeks of virtue signaling.

I’m personally quite excited about the possibilities of generative AI for game dev, but mostly keep it to myself because I *know* exactly what the reaction will be.