Writers Should Ask for More

Steven Levy thinks writers have to choose between going it alone or working for a legacy publication. But new and better models are emerging.

Hello! For all the new readers: I’m Ryan Rigney and this is Push to Talk, a weekly newsletter that’s normally about the art and business of video games. Today’s piece is a detour from games into another topic I’ve been thinking about lately: the weirdly limited way some legacy media voices view Substack’s place in the media ecosystem.

It’s funny how easy it is to compress our lives down into simple stories.

Like when people ask what I did before my current job, I usually just say “I worked as a marketing guy in the video game industry for a decade, and before that I wrote about games for magazines.”

That summary omits some emotionally-charged personal lore.

For one, the magazines thing: I was obsessed with games magazines as a kid. Tips & Tricks was useful. Electronic Gaming Monthly was more mature and eclectic. Game Informer was polished and beautiful. But the real magic was in Nintendo Power, which was just as colorful and joyful as the games it promoted. Its writers and reviewers had real personality, and the magazine celebrated them by name. It even included a stack-ranked diagram to inform you about each reviewer’s preferred genres. I daydreamed: How cool would it be to review games for a living?

Around the time I got to high school, I decided it was time to grow up and read some real magazines. My journalism teacher was a classic 90s-style techno-libertarian who shared his copies of Wired Magazine with me. The writing in Wired was best-in-class, this teacher explained. He heaped particular praise on the feature stories, many of them written by “editor at large” Steven Levy. I studied those pieces like they were sacred texts. I wanted to write like Levy. And when I told my teacher about my ambitions to one day write for magazines, he said “if you ever write for Wired I’ll hang your picture on the wall.”

That gave me a north star to aim for, and his encouragement was fuel in my tank. Three years later, I got my first feature story published in Wired.

Okay, technically it was on Wired.com. But it sounds so much nicer if I compress the story down, doesn’t it? The point is, I learned how to write in large part by studying Wired feature stories, and the Wired house style for features is fundamentally Steven Levy’s DNA. He’s written far more features for the magazine than anyone else, with his first Wired piece appearing all the way back in Volume 1, Issue #2, in 1993.

Still, 32 years later, Levy is writing for Wired. He remains, at age 74, a fantastic writer. But last Friday he wrote a piece about Substack that I fervently disagree with. And I think the problem is that, like many who’ve invested years of their lives into the legacy media ecosystem, Levy has adopted an overly-compressed, simplified, and ultimately incorrect narrative about what Substack and other platforms like it (Ghost, Beehiiv, Patreon, Kit, etc.) actually are.1

The Old-School Sneaks In

Levy’s story (linked above) starts out with a rundown of all the former TV news hosts and newspaper journalists who’ve recently made the move to Substack: Terry Moran, Jennifer Rubin, Mehdi Hassan, Chuck Todd. You can check the Substack leaderboards for the U.S. History category to see a whole list of people like this. You’ve got 1960s-era TV legends like Dan Rather and social media age grifters like Shaun King, all on one platform.

After this intro, Levy quickly launches his attack:

You might be tempted to think that the Substack revolution is shaking up the foundations of journalism, agreeing with Substack star Emily Sundberg that newsroom leaders everywhere should be barring their doors to prevent further defections. Well, not so fast. The Substack model may work very well for a few, but it’s not so easy to march in and match a salary. Readers have to pay a high price for a voice that they once enjoyed in a publication they subscribe to. And writers have to get used to the idea that the breadth of their wisdom is limited to a small percentage of patrons. Is Substack sustainable for writers addressing a general audience?

This paragraph acts as the framing for the rest of the piece, and it fundamentally sucks as a starting point. Levy is right, of course, that very few who leave a full-time job and open up a Substack will immediately match their former salary. And the cost for readers is higher on a per-writer basis, yes. But the last two sentences are where he loses the thread.

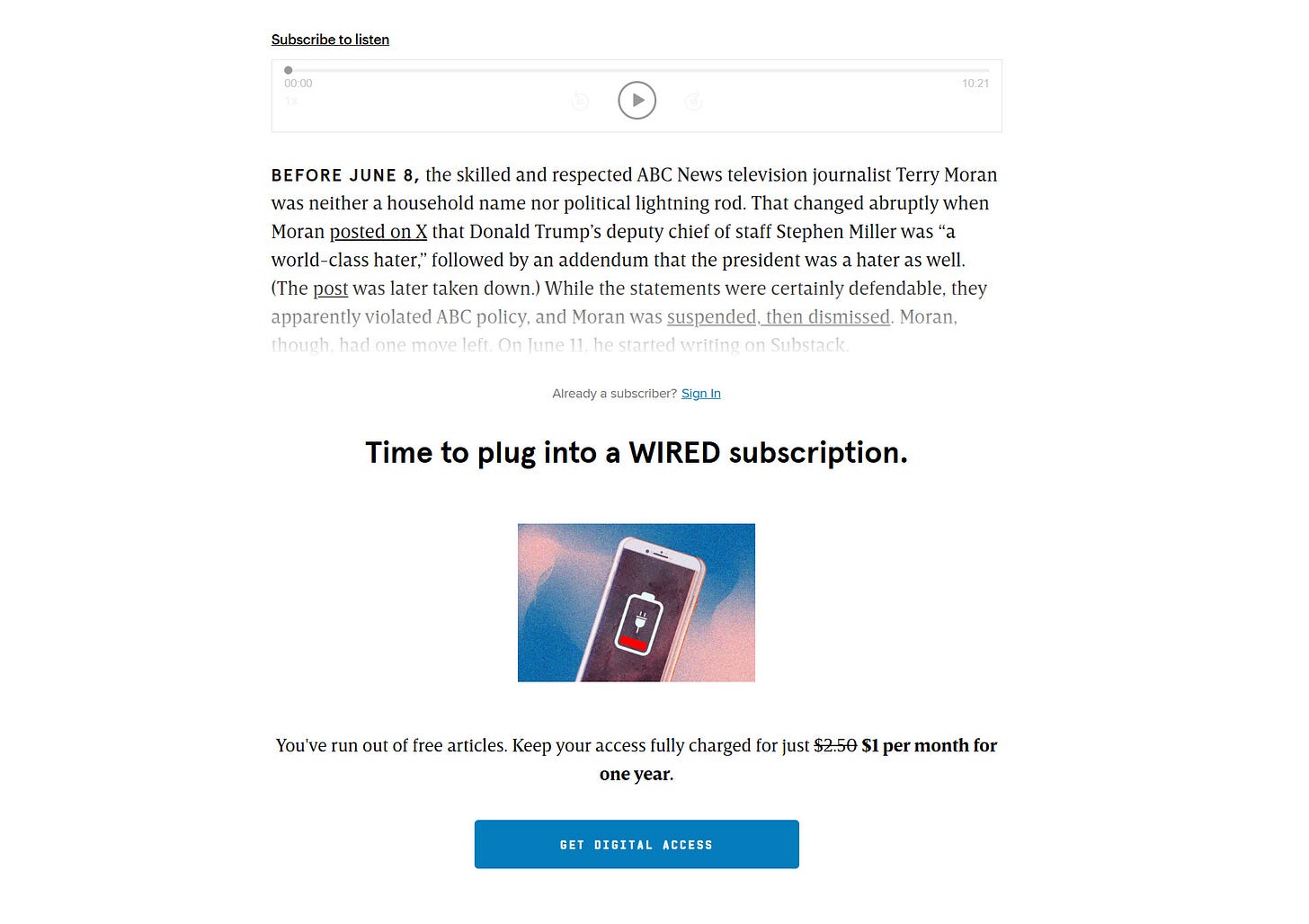

First, what’s this about the wisdom of writers being “limited to a small percentage of patrons?” If Levy is referencing paywalls on Substack locking content off from free readers, he might be concerned to learn that this is what his own column looks like for non-paying Wired readers:

I’m being rude here. Obviously Levy knows that his newsletter is locked behind a paywall. But then why bring up paywalls as a criticism of Substack?

Regardless, the question he raises next is more revealing: Is Substack sustainable for writers addressing a general audience? I mean, the answer to this is very simply: No. A general audience? What? That’s not what Substack is. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the business model.

Substack is a platform that rewards writers who address extremely specific niches. Isn’t that obvious? Just look at the leaderboards for the top paid newsletters. The number one newsletter in the business category is a career advice blog for product managers at tech companies. One of the three biggest writers in the technology category is Alex Xu, who writes a highly technical blog about systems design for software engineers. The biggest Substack about U.S. politics is a digital news ‘zine specifically targeting center-right conservative types who are anti-woke (huge audience!) but also anti-Trump (uh-oh?) and basically classically liberal in outlook and which runs columns with headlines like My Husband Wants to Be Cremated. I’d Ignore His Dying Wish.

Who is the target demographic here? I dunno man, but it works on Substack. And that’s because, unlike in print magazines or their erstwhile dot-com successors, the most successful Substacks are not trying to serve a general audience. They’re fundamentally niche publications where highly qualified writers serve a targeted audience best-in-class content about a specific well-defined topic. And they often ship multiple times per week, or even daily. (One more case-in-point: the #9 best-selling culture newsletter is a hyper-focused feminist perspective newsletter about abortion called, somewhat threateningly, Abortion, Every Day.)

All of that is to say: Levy is asking the wrong question. But he’s not alone in this misunderstanding. Here he goes quoting another writer who’s equally confused:

Ana Marie Cox, who once enjoyed blogging fame as Wonkette, is even grimmer, writing in her newsletter that Substack “is as unstable as a SpaceX launch.” She wasn’t impressed with the more recent influx of name writers. “How many Terry Morans does Substack have room for?” she wrote. “Is there even a public appetite for a dozen Terry Morans, each independently Terry Moran-ing in his own newsletter?”

Cox is referring to subscription fatigue, which is something I think of every time a sign-up page pops up when opening a new Substack. Typically, Substack pros solicit a monthly fee of $5-10 or an annual rate of $50-150. Usually there’s a free tier of content, but journalists who hope to make at least part of their livelihood on Substack save the good stuff for paid customers. Compared to subscribing to full-fledged publications, this is a terrible value proposition. After leaving The Atlantic, celebrated writer Derek Thompson started a Substack that cost $80 a year—that’s one penny more than a digital subscription to the magazine he just left! (The Atlantic will probably spend $300,000 to replace him with someone else worth reading.) It doesn’t take too many of those subscriptions to match the cost of The New York Times, which probably has 100 journalists as good as Substack writers, and you get Wordle to boot.

We’ve got a few things to deal with here:

It’s extremely funny to randomly diss Ana Marie Cox as someone who “once enjoyed blogging fame.” That’s just a brutal left hook out of nowhere from Levy.

I’ll match Levy with a swing of my own: Cox’s quip that Substack is “as unstable as a SpaceX launch” is such a BlueSky-coded way of saying she hopes it fails. It’s a line that only makes sense if your brain has been totally melted by viewing everything through a lens distorted by politics and culture wars.

But the real banger line here is Levy’s own argument that “Compared to subscribing to full-fledged publications,” paying $80/year for a publication run by a single writer is “a terrible value proposition.”

This last one is what I want to focus on, because the math here is illustrative of the real difference between Substack and other subscription-powered legacy media outlets.

Remember that screenshot above showing how Steven Levy’s newsletter is hidden behind a paywall? Here’s what you see when you click that beautiful blue “GET DIGITAL ACCESS” button:

Wow! $1 per month for access. And after the first year it’s still only $30/year! That’s like, less than half of what you’d pay for an annual sub to a single premium Substack. What value! Time to click that “GET DIGITAL ACCESS” button for a second time. But wait, what’s this?

That first-year discount is pretty steep: $5/month total for seven different media outlets. Why is Wired corporate owner Condé Nast offering me such a big discount to subscribe to a bunch of completely unrelated publications? I mean, what does the actual Venn diagram look like between Wired subscribers and Vogue readers? I’m sure it’s not nothing but is there really that much of an overlap?

Ads World vs. Subs World

Here’s what’s actually happening:

Yes, Condé Nast would like to onboard a bunch of inattentive subscribers for cheap and then automatically renew them at $144/year. That’s part of this. But more than that, they’re pricing their first-year subscriptions low because they need to be able to tell advertisers that they’ll put their ads in front of a lot of eyeballs. Steven Levy’s newsletter does not pay for itself by generating subscription revenue. How could it? Each Wired subscriber is paying less than $3/month. Instead, the Condé Nast business model is built around charging corporate buyers high CPM rates for ad units which are displayed across Condé’s entire portfolio of brands. The more people viewing these publications—or passively subscribed to them—the more they can charge.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this business model,2 but Condé’s approach has fundamentally different economic incentives from something like Substack. If your primary business is “selling a ton of ad volume to corporate buyers,” you’re going to need to create content designed to reach a big, general audience.

That’s different from Substack. Because the primary revenue driver here is subscription-based, a solo writer can get by with a much smaller readership. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing something so niche that only a few thousand people care about it. If the work is good enough that you can convince 1,000 people to pay $8/month for it, you’re in business. Scale up from there to 2,000 subs, and you’re almost certainly getting paid better than the median Wired writer.3

This is really important: To make its business work The Atlantic needs hundreds of thousands of readers who may or may not care about their content. Derek Thompson only needs a few thousand people to really care about his abundance thing. These are totally different business models, with very different incentives.

Often, when writers for legacy media outlets write about Substack, they do this thing where they adopt an objective-sounding tone in order to appear authoritative. They bring in outside “experts” for quotes, and copiously link to other media commentators for backup. If you read between the lines in these pieces, you see that these writers are using the process of writing the article to work out for themselves what it would take for them to start a Substack. Levy is absolutely doing the same thing here. And he gives the game away when he slips in, parenthetically, that he has made a “conscious choice” to stick with Condé Nast. As he puts it:

You will note that this newsletter, and this writer, are delivered to you as part of a larger legacy media stack. That’s a conscious choice.

What calculations informed this choice? Levy doesn’t tell us. That’s somewhat understandable, as it would probably require sharing his current comp package at Wired, where Levy is almost certainly the highest-paid writer on staff (at least, I hope that’s the case). Again, the guy has been writing for this same magazine since before Doom released. The opportunity cost of leaving Wired and starting fresh with an “indie newsletter,” as he puts it, is gonna be way higher for Levy than it would be for any less tenured writer on staff.

A False Dichotomy

This is where I think we have to question Levy’s original framing: the idea that “time is running out” for anyone that wants to build a career on Substack. The argument hinges on the assumption that in order to be successful on Substack, you have to be a big hotshot who leaves a legacy media publication to go all-in as a solo writer.

In practice, there are a much wider variety of things happening on the platform:

Writers like Katherine Dee freelance for legacy pubs and use those opportunities as a way to drive more awareness for owned channels

Journalists who are happily committed to a big media brand like Bloomberg’s Jason Schreier operate a non-paid Substack to promote books and other side projects.

Experienced media people who’ve successfully scaled a newsletter on Substack like Stephen Totilo are starting to bring in additional freelance writers to increase the output on their (formerly solo) publications.

Before it was bought and gutted by Valnet, I had a deal with Polygon to syndicate some of the feature stories written here for Push to Talk. They offered to pay, but I turned them down because I just wanted the additional distribution and reach for my work.

The point is: there are new models and possible arrangements emerging. Writers no longer have to choose between a full-time stable job at a legacy publication and going for broke alone on Substack. Some go all in and make it work. Some treat Substack like another social channel, dipping their toes in and building up reach while keeping one or even two feet in a more traditional arrangement.

Substack doesn’t yet solve everything. Far from it, actually. The macro-environment sucks for most professional writers. But if you squint, you can see a new ecosystem evolving—one where scrappy writers are claiming freedom for themselves to capture more of the value they create. I strongly believe that part of this evolution will include the emergence of new outlets that can employ freelancers and help newer writers get started.

So there’s a false dichotomy that’s been presented to writers. And even if you accept the terms of that split, Levy admits, some of those solo Substack writers are worth paying for. Not that jerk Terry Moran, of course. “No way will I pay him,” Levy writes, before listing some writers he subscribes to:

I’ve already got ABC News on my cable, paid subscriptions to nearly a dozen publications and, yes, a bunch of Substack subs that I or my wife get billed for yearly or monthly. These include James Fallows, Jonathan Alter, Joyce Wadler, and Gregg Easterbrook, during the months he writes Tuesday Morning Quarterback.

Even though the price is high for one single voice, I find those writers worth the cost…

Nice! But wait. There’s one more sentence in this article, and it’s here that Levy slips in one little request—a poison pill revealing that his thinking about media is fundamentally stuck in 1993:

But I wish the legacy publications they once wrote for still employed them so I wouldn’t have to pay a la carte.

Oh my God. Yes. The problem with Substack is that you can just pay writers directly and they keep 87% of the money.4 This can’t stand. In fact, every time I get paid I think to myself I just wish that I could somehow cut a Condé Nast executive in on this. You know? I don’t feel right making a dollar unless at least half of it goes to some guy sitting in a New York City corner office.

How can anyone working in media read this and not pull their hair out? Levy just admitted that these writers are worth the cost. Now he wishes they’d give up some significant percentage of their revenue to a middleman “legacy publication” (his words, not mine!) just so the billing is cleaner?

I’m just gonna say it: Steven Levy ought to be able to start a paid Substack—or any side hustle he wants—while still keeping that Wired gig. If he did, thousands of people would doubtless decide that he’s worth $8/month, “subscription fatigue” be damned. I know I would. So why not do it? Does he think he needs Condé Nast to act as a mediator for all the words he publishes on this side of eternity? Or is it just fear holding him and many other legacy media writers like him back?

Maybe Levy has compressed his own story down into something too simple: Wired editor-at-large. That’s a good story. But he’s more than that.

To be clear, I don’t dismiss the “subscription fatigue” thing. I’m subscribed to too many Substacks as well, and I also feel like I’m hitting my limit on paid subs. But why is the only suggested solution here for writers to cut in some billion-dollar conglomerate on every subscription? That is hopelessly old-school thinking.

Here’s another idea: Substack could let readers opt into a cable-TV style approach to billing: Customize your subscription bundle with different packages and channels, and get billed one flat rate once per month. One subscription, with all the writers you truly want to hear from. That’s just one idea! I’m just throwing stuff out here. Surely, surely there are other solutions here that don’t involve dragging in the bloated, advertising-addicted corpses of a bunch of 20th century media companies.

In the meantime, writers have got to break out of this 20th century mode of thinking that you can only do one thing at a time. You ought to be able to try radical new ways of distributing your work and building up your own channels—even if doing so while still working for “the man.”

It’s time to ask for more.

That’s it for this week.

I’m gonna go unsubscribe from Bon Appétit.

A disclosure: I have no personal financial interest in Substack but I work at a16z, which has led investments into the company. Every argument I make here in favor of Substack applies just as cleanly to competitors like Ghost, Beehiiv, Patreon, and Kit.

I mean… maybe there is? But it’s a well-established way of running media companies.

Some napkin math: 2,000 × $8/mo × 12 × 87% ≈ $167k. Glassdoor says Staff Writer pay at Wired tops out at $89k a year.

Minus Substack’s 10% fee and Stripe’s 2.9% take

Hey thanks so much for this, very insightful and uplifting in a way. Gonna go continue working on my Substack to one day hit the 2000K monthly subs 😃

Good piece! A few minor quibbles:

1) When I worked at a magazine ~6 years ago ads were already not the "primary business." I'm sure for some of the mags in Conde's portfolio (the glossy ones with premium ads for pricey brands) ad revenue brings in a meaningful amount of money but I think subscriptions are the name of the game (though less so than on Substack). Just don't think the distinction is *that* stark (and also, a lot of these brands make money in like... 10 different ways: ads, subs, events, consulting, etc.)

2) I think the weaknesses in Levy's argument come out when he tries to be most specific, but I assume the main thing he is articulating is the same thing Jerry Saltz was saying when he turned down a big Substack paycheck. He said:

"Substack just offered me $250,000 a year to go with them. That is more than double what I make. More money than I have ever have or dreamt of having. Yet, I said no. How come? I think it’s fishy to always be barking to your readers to subscribe. I think it is not my real work to write fir “subscribers.” My only work is to write for the reader. ... I want to reach strangers; be loved and hated by strangers; talk about art to anyone any where any how. I like being in my huge department store @/Nymag where people find me who have no idea who I am or what I do or even thought about art before."

I think this is a clearer articulation of the "general audiences" thing than Levy offers. Depending on your POV this is either snobbish or high-minded and sweet, but I think Levy (and probably Saltz) would feel a bit put-off by the idea of being lumped in with "a career advice blog for product managers at tech companies." They have a different idea of who they want to serve and for what reason. (As I type that I realize that's maybe a bit of a contrived connection but I think "serving niches," which you identify as a strength, is maybe a bit anathema to a former print journalist used to being read in conversation/sequence with other writers vetted by like-minded editors and stylists.)