YouTubers Can't Save All the Indie Games

“The systems we have available just aren't built for this kind of volume.”

Hi to all the new readers: I’m Ryan Rigney and this is Push to Talk, a weekly newsletter about the art and business of video games. Today we’re taking a look at the impossible challenge facing YouTubers who want to help great indie games get discovered.

There are not all that many similarities between the video game business and the world of book publishing. But last year a very similar crisis struck both.

It’s a problem of too many and not enough. Too many games/books, and not enough players/readers. In both cases, an overabundance of content is being met with growing apathy.

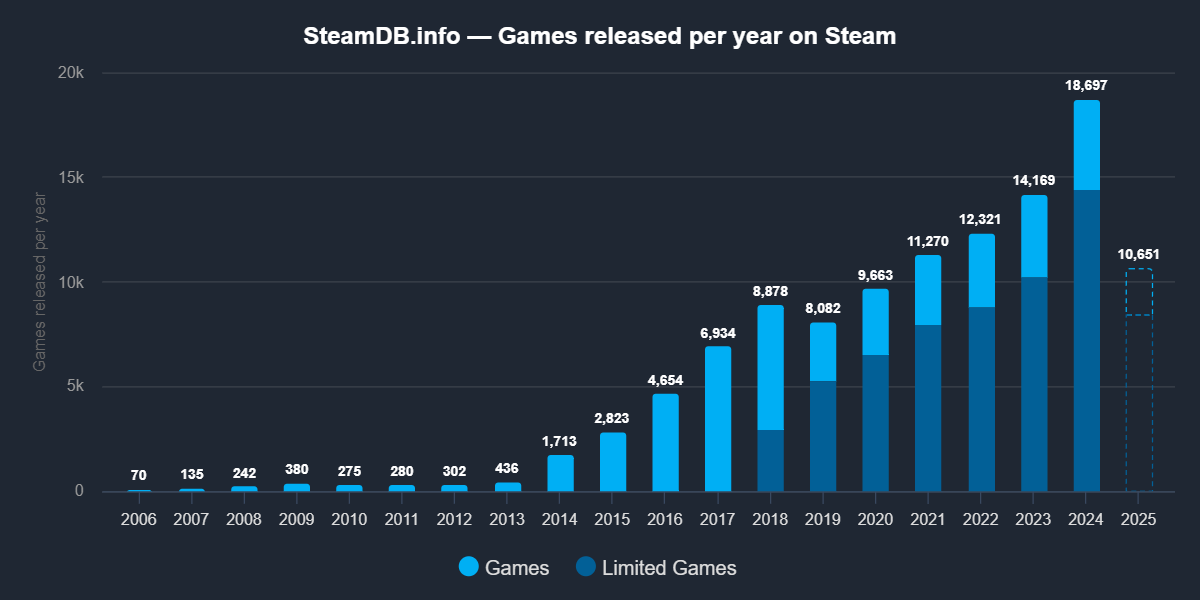

For instance: More games than ever were released on Steam last year, while the number of games earning over 1,000 reviews (one reasonable proxy for success) didn’t change much. There are more games than ever, and the same number of winners.

Meanwhile over in the book biz, the news is worse. In a viral essay last year titled “No one buys books,” Substack writer Elle Griffin shared data from a 2022 antitrust lawsuit against Penguin Random House suggesting that half of professionally-published books in the United States sell fewer than a dozen copies. Only 10 percent sell more than 2,000 copies. And what about the biggest hits? Out of the many hundreds of thousands of new, traditionally published books each year, the CEO of Penguin Random House testified that probably only around 50 sell more than 500,000 copies.1

This is a problem that’s bigger than books or games. Supply of new creative works of almost all types is outpacing demand for those works.

In the process, many institutions that were built specifically to help people make sense of the world’s creative output are beginning to break down.

YouTube: The Magic Games Marketing Machine

One of the many differences between the books and games industries has to do with the size and vitality of the media environment surrounding them.

BookTok can drive sales of books, sure. But it’s small potatoes compared to gaming’s dominance on YouTube, where creators with millions of subscribers use the “Let’s Play” format to make millions of viewers aware of new games on a daily basis.

YouTube’s importance to the games ecosystem really can’t be overstated: Nearly two-thirds (64%) of surveyed gamers say YouTube is the place they go to find out about new games.2 And as we saw in last week’s post about Balatro, game developers often credit YouTubers when explaining how their games went viral.

But no media institution remains dominant forever. In fact, each of the past three decades has seen a handoff from one form of media to another:

In the 90s, print magazines were the primary media institution that helped players make sense of the creative output of the video game industry.

In the 2000s, this role shifted over to websites and blogs like IGN (founded in 1996), GameSpot (also ‘96), Eurogamer (1999) and Kotaku (2004).

In the 2010s, the websites and blogs gave way to the rise of streamers and YouTubers. Twitch launched in 2011. PewDiePie became the most-subscribed-to channel on YouTube in 2013, and a million Let’s Play channels followed. By the end of the decade the handoff was complete. YouTube was undeniably the primary media institution for people who wanted to find out about games.

Now, as the number of games released annually rises, YouTubers—especially those who go out of their way to cover independent games—are struggling to keep up.

Take Wanderbot for example. He’s a YouTuber with 500,000 subscribers who says he’s “on a personal mission to play as many cool videogames as humanly (or inhumanly) possible.” Wanderbot tells Push to Talk that in the 11 years he’s been running his channel, it’s never been harder to keep up with games.

“My pitches per day have gone up massively since about 2019 or so,” he said in an email exchange. “Pre-2020, I felt great if I could find 1-2 new games per week that fit my interests/niche/bare minimum requirements for quality, which worked fine when I was still doing Let's Plays. Post-2020, the sheer quantity of new releases is so high that I can only cover roughly 10-25% of games that fit those same criteria, and only as a one-off impressions video rather than a full playthrough.”

One thing that has changed dramatically in recent years is the popularity of “outreach lists” for content creators. Because Wanderbot has over half a million subscribers, his contact info is automatically included on many outreach lists.

As a result, “I get a minimum of ~30 emails per day from unique developers who are either asking for coverage or just trying to catch my interest,” he says.

That’s during normal times. During major events like Steam Next Fest, Wanderbot says he sometimes gets over 100 pitch emails per day. This has become such a problem that he’s begun searching for some sort of filtering solution to cut down on the noise. He says that he’s considering making a second email address for developers, PR reps, and publishers that he already knows and trusts so he can “prioritize people who I generally trust to send me decent games.”

Ultimately, the sheer number of new games has come to feel like a burden, even for someone like Wanderbot who is explicitly looking for new games to play and feature: “To be honest, I'm not really excited for how much the release numbers are scaling up for this year and going into the future,” he says. “The systems we have available just aren't built for this kind of volume.”

Sidebar: The Machine Breaks Down

I’ve written at length already about the evolution of sponsored streams, which have become the go-to way for games marketers with a budget to guarantee coverage of new titles from otherwise overwhelmed streamers.

As more marketing money entered the streaming landscape, and competitive pressures ramped up, some smaller developers have begun to feel that they have no choice but to also spend on streamer attention. This, however, is not really a workable solution.

Oriol Cosp Arqué is a game dev behind titles like The Ouroboros King (2023) and Gods vs Horrors (2025). One of the things Arqué has noticed is that the expected value from views of games on YouTube is lower than you might expect, leading him to argue that the streamer sponsorship model is broken.

“Gods vs Horrors got relatively low coverage during development,” he tells Push to Talk, “and after seeing fellow indies in the genre sponsoring content creators, I decided to run a sponsorship campaign too. I made sponsorship offers to 45 creators based on sharing 50% of the value I expected to get from the streams and was declined by all except the two streamers who had previously played the game (which would have probably played the game on release). I'm probably never actively seeking sponsorships again.”

Ultimately, Arqué arrived at the same assessment of sponsored streams and VODs that even many bigger-budget marketing departments have come to in recent years: “The sponsorship prices are too high compared to the value they provide to indie devs.”

Pop Off, Player

Imagine the world from a big YouTuber’s perspective.

If you think about gaming’s too many and not enough problem, one thing quickly becomes clear: There isn’t actually much incentive to be the first to cover a new game.

There are some qualifications one could make here. It’s not good to be weeks late to a new title, because then you risk boring the audience with something they’ve already grown tired of. But if you’re the very first person to stream a game, you have to overcome the same hurdle game developers themselves face: convincing players that a new game is worth their time and attention. You don’t even know whether the demand is going to be there.

You’d much rather be able to start off a video by saying “alright, a lot of you in the comments and the Discord have been begging me to play this game, so I’m giving it a shot.”

Remember, supply of new games is outpacing demand for new games. This causes problems for YouTubers, too. Like devs, they also operate in a world driven by demand for games. They just capture it at an earlier stage of the funnel. So creators are incentivized to put their creative energy toward covering games that already have proven demand—not unlike a publisher or investor!

A lot of indie devs have the mistaken perception that their game will “pop off” if a big enough YouTuber plays it. Increasingly, things are working in the exact reverse order. Because most YouTubers can only afford to play a few of the many games sent their way, they will naturally prioritize games that are already popping off.

But then who will sort through all the new games to help the really great ones get discovered in the first place?

I asked Wanderbot how he thinks about his own role in the games ecosystem. Is it primarily as entertainment for viewers? Or is there also some element of hoping to lift up indie devs?

“Back when I was doing Let's Play series, I definitely saw myself primarily as entertainment while still trying to uplift indie devs,” he wrote back. “Now it's definitely the latter… in light of how miserable corporate AAA development seems to be (especially with the recent layoffs) it feels like the best thing I can do for the games industry is to highlight and uplift as many indie developers/games as possible.”

Nobody can save all the indie games. But it’s nice that someone is trying.

That’s it for this week.

I’m gonna go play one of the 37 roguelikes that came out since Monday.

This was part three in a series of pieces examining the game dev > YouTuber > player pipeline.

Check out part one: How to Get YouTubers to Play Your Game

And part two: The Word-of-Mouth Magic Behind Breakout Hits Like Balatro

For comparison, roughly 110 games released in 2024 on Steam alone managed to sell over 500,000 copies. (Source: Data available via the GameDiscoverCo+ tool)

Source: Big Games Machine’s How Gamers Discover What to Play in 2024 report.

I highly suggest people look at Remap's Steam Vent feature, wherein they play games on the Recently Added page rather than other list such as Trending. They've found some gems, while also highlighting how broken discoverability is on platform like Steam.

While it is not a great solution like many of these YouTube features, it's attempting to do something different. Remap has also shown just how many new games have AI content disclosures on Steam.

Brilliantly written. Amazing insights. Thanks for shedding light on this.